Email

New York tried to restrict prison journalism...what about other states?

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | New York tried to restrict prison journalism...what about other states? |

| Date | June 15, 2023 2:46 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

A web of complex and vague policies make prison journalism extremely difficult and sometimes risky

Prison Policy Initiative updates for June 15, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Breaking news from inside: How prisons suppress prison journalism [[link removed]] Building on data from the Prison Journalism Project, we find that most states enforce restrictions that make practicing journalism extremely difficult and sometimes risky. [[link removed]]

by Brian Nam-Sonenstein

Last month, New York prison officials introduced a policy [[link removed]] to effectively suppress prison journalism. It went unnoticed for a few weeks until reporters at NYS Focus caught wind of it. A righteous backlash ensued, forcing the department to rescind the policy [[link removed]] for the time being.

Prisons don't want you to know what happens inside. That's what makes prison journalism so important.The incident left many people wondering: how common are restrictions on prison journalism? Building on data compiled by the Prison Journalism Project [[link removed]], we scoured handbooks, prison policies, and laws governing every corrections department in the U.S. to try and find out.

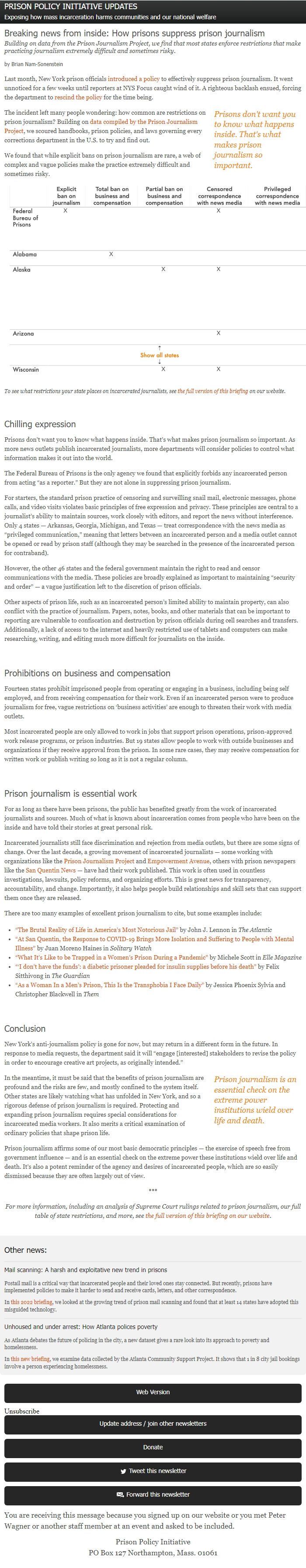

We found that while explicit bans on prison journalism are rare, a web of complex and vague policies make the practice extremely difficult and sometimes risky.

To see what restrictions your state places on incarcerated journalists, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Chilling expression

Prisons don’t want you to know what happens inside. That’s what makes prison journalism so important. As more news outlets publish incarcerated journalists, more departments will consider policies to control what information makes it out into the world.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons is the only agency we found that explicitly forbids any incarcerated person from acting “as a reporter.” But they are not alone in suppressing prison journalism.

For starters, the standard prison practice of censoring and surveilling snail mail, electronic messages, phone calls, and video visits violates basic principles of free expression and privacy. These principles are central to a journalist’s ability to maintain sources, work closely with editors, and report the news without interference. Only 4 states — Arkansas, Georgia, Michigan, and Texas — treat correspondence with the news media as “privileged communication,” meaning that letters between an incarcerated person and a media outlet cannot be opened or read by prison staff (although they may be searched in the presence of the incarcerated person for contraband).

However, the other 46 states and the federal government maintain the right to read and censor communications with the media. These policies are broadly explained as important to maintaining “security and order” — a vague justification left to the discretion of prison officials.

Other aspects of prison life, such as an incarcerated person’s limited ability to maintain property, can also conflict with the practice of journalism. Papers, notes, books, and other materials that can be important to reporting are vulnerable to confiscation and destruction by prison officials during cell searches and transfers. Additionally, a lack of access to the internet and heavily restricted use of tablets and computers can make researching, writing, and editing much more difficult for journalists on the inside.

Prohibitions on business and compensation

Fourteen states prohibit imprisoned people from operating or engaging in a business, including being self employed, and from receiving compensation for their work. Even if an incarcerated person were to produce journalism for free, vague restrictions on ‘business activities’ are enough to threaten their work with media outlets.

Most incarcerated people are only allowed to work in jobs that support prison operations, prison-approved work release programs, or prison industries. But 19 states allow people to work with outside businesses and organizations if they receive approval from the prison. In some rare cases, they may receive compensation for written work or publish writing so long as it is not a regular column.

Prison journalism is essential work

For as long as there have been prisons, the public has benefited greatly from the work of incarcerated journalists and sources. Much of what is known about incarceration comes from people who have been on the inside and have told their stories at great personal risk.

Incarcerated journalists still face discrimination and rejection from media outlets, but there are some signs of change. Over the last decade, a growing movement of incarcerated journalists — some working with organizations like the Prison Journalism Project [[link removed]] and Empowerment Avenue [[link removed]], others with prison newspapers like the San Quentin News [[link removed]] — have had their work published. This work is often used in countless investigations, lawsuits, policy reforms, and organizing efforts. This is great news for transparency, accountability, and change. Importantly, it also helps people build relationships and skill sets that can support them once they are released.

There are too many examples of excellent prison journalism to cite, but some examples include:

“The Brutal Reality of Life in America’s Most Notorious Jail” [[link removed]] by John J. Lennon in The Atlantic “At San Quentin, the Response to COVID-19 Brings More Isolation and Suffering to People with Mental Illness” [[link removed]] by Juan Moreno Haines in Solitary Watch “What It’s Like to be Trapped in a Women’s Prison During a Pandemic” [[link removed]] by Michele Scott in Elle Magazine “ [[link removed]] ‘I don’t have the funds’: a diabetic prisoner pleaded for insulin supplies before his death” [[link removed]] by Felix Sitthivong in The Guardian “As a Woman In a Men’s Prison, This Is the Transphobia I Face Daily” [[link removed]] by Jessica Phoenix Sylvia and Christopher Blackwell in Them

Conclusion

New York’s anti-journalism policy is gone for now, but may return in a different form in the future. In response to media requests, the department said it will “engage [interested] stakeholders to revise the policy in order to encourage creative art projects, as originally intended.”

Prison journalism is an essential check on the extreme power institutions wield over life and death.

In the meantime, it must be said that the benefits of prison journalism are profound and the risks are few, and mostly confined to the system itself. Other states are likely watching what has unfolded in New York, and so a rigorous defense of prison journalism is required. Protecting and expanding prison journalism requires special considerations for incarcerated media workers. It also merits a critical examination of ordinary policies that shape prison life.

Prison journalism affirms some of our most basic democratic principles — the exercise of speech free from government influence — and is an essential check on the extreme power these institutions wield over life and death. It’s also a potent reminder of the agency and desires of incarcerated people, which are so easily dismissed because they are often largely out of view.

***

For more information, including an analysis of Supreme Court rulings related to prison journalism, our full table of state restrictions, and more, see the full version of this briefing on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mail scanning: A harsh and exploitative new trend in prisons [[link removed]]

Postail mail is a critical way that incarcerated people and their loved ones stay connected. But recently, prisons have implemented policies to make it harder to send and receive cards, letters, and other correspondence.

In this 2022 briefing [[link removed]], we looked at the growing trend of prison mail scanning and found that at least 14 states have adopted this misguided technology.

Unhoused and under arrest: How Atlanta polices poverty [[link removed]]

As Atlanta debates the future of policing in the city, a new dataset gives a rare look into its approach to poverty and homelessness.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we examine data collected by the Atlanta Community Support Project. It shows that 1 in 8 city jail bookings involve a person experiencing homelessness.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for June 15, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Breaking news from inside: How prisons suppress prison journalism [[link removed]] Building on data from the Prison Journalism Project, we find that most states enforce restrictions that make practicing journalism extremely difficult and sometimes risky. [[link removed]]

by Brian Nam-Sonenstein

Last month, New York prison officials introduced a policy [[link removed]] to effectively suppress prison journalism. It went unnoticed for a few weeks until reporters at NYS Focus caught wind of it. A righteous backlash ensued, forcing the department to rescind the policy [[link removed]] for the time being.

Prisons don't want you to know what happens inside. That's what makes prison journalism so important.The incident left many people wondering: how common are restrictions on prison journalism? Building on data compiled by the Prison Journalism Project [[link removed]], we scoured handbooks, prison policies, and laws governing every corrections department in the U.S. to try and find out.

We found that while explicit bans on prison journalism are rare, a web of complex and vague policies make the practice extremely difficult and sometimes risky.

To see what restrictions your state places on incarcerated journalists, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Chilling expression

Prisons don’t want you to know what happens inside. That’s what makes prison journalism so important. As more news outlets publish incarcerated journalists, more departments will consider policies to control what information makes it out into the world.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons is the only agency we found that explicitly forbids any incarcerated person from acting “as a reporter.” But they are not alone in suppressing prison journalism.

For starters, the standard prison practice of censoring and surveilling snail mail, electronic messages, phone calls, and video visits violates basic principles of free expression and privacy. These principles are central to a journalist’s ability to maintain sources, work closely with editors, and report the news without interference. Only 4 states — Arkansas, Georgia, Michigan, and Texas — treat correspondence with the news media as “privileged communication,” meaning that letters between an incarcerated person and a media outlet cannot be opened or read by prison staff (although they may be searched in the presence of the incarcerated person for contraband).

However, the other 46 states and the federal government maintain the right to read and censor communications with the media. These policies are broadly explained as important to maintaining “security and order” — a vague justification left to the discretion of prison officials.

Other aspects of prison life, such as an incarcerated person’s limited ability to maintain property, can also conflict with the practice of journalism. Papers, notes, books, and other materials that can be important to reporting are vulnerable to confiscation and destruction by prison officials during cell searches and transfers. Additionally, a lack of access to the internet and heavily restricted use of tablets and computers can make researching, writing, and editing much more difficult for journalists on the inside.

Prohibitions on business and compensation

Fourteen states prohibit imprisoned people from operating or engaging in a business, including being self employed, and from receiving compensation for their work. Even if an incarcerated person were to produce journalism for free, vague restrictions on ‘business activities’ are enough to threaten their work with media outlets.

Most incarcerated people are only allowed to work in jobs that support prison operations, prison-approved work release programs, or prison industries. But 19 states allow people to work with outside businesses and organizations if they receive approval from the prison. In some rare cases, they may receive compensation for written work or publish writing so long as it is not a regular column.

Prison journalism is essential work

For as long as there have been prisons, the public has benefited greatly from the work of incarcerated journalists and sources. Much of what is known about incarceration comes from people who have been on the inside and have told their stories at great personal risk.

Incarcerated journalists still face discrimination and rejection from media outlets, but there are some signs of change. Over the last decade, a growing movement of incarcerated journalists — some working with organizations like the Prison Journalism Project [[link removed]] and Empowerment Avenue [[link removed]], others with prison newspapers like the San Quentin News [[link removed]] — have had their work published. This work is often used in countless investigations, lawsuits, policy reforms, and organizing efforts. This is great news for transparency, accountability, and change. Importantly, it also helps people build relationships and skill sets that can support them once they are released.

There are too many examples of excellent prison journalism to cite, but some examples include:

“The Brutal Reality of Life in America’s Most Notorious Jail” [[link removed]] by John J. Lennon in The Atlantic “At San Quentin, the Response to COVID-19 Brings More Isolation and Suffering to People with Mental Illness” [[link removed]] by Juan Moreno Haines in Solitary Watch “What It’s Like to be Trapped in a Women’s Prison During a Pandemic” [[link removed]] by Michele Scott in Elle Magazine “ [[link removed]] ‘I don’t have the funds’: a diabetic prisoner pleaded for insulin supplies before his death” [[link removed]] by Felix Sitthivong in The Guardian “As a Woman In a Men’s Prison, This Is the Transphobia I Face Daily” [[link removed]] by Jessica Phoenix Sylvia and Christopher Blackwell in Them

Conclusion

New York’s anti-journalism policy is gone for now, but may return in a different form in the future. In response to media requests, the department said it will “engage [interested] stakeholders to revise the policy in order to encourage creative art projects, as originally intended.”

Prison journalism is an essential check on the extreme power institutions wield over life and death.

In the meantime, it must be said that the benefits of prison journalism are profound and the risks are few, and mostly confined to the system itself. Other states are likely watching what has unfolded in New York, and so a rigorous defense of prison journalism is required. Protecting and expanding prison journalism requires special considerations for incarcerated media workers. It also merits a critical examination of ordinary policies that shape prison life.

Prison journalism affirms some of our most basic democratic principles — the exercise of speech free from government influence — and is an essential check on the extreme power these institutions wield over life and death. It’s also a potent reminder of the agency and desires of incarcerated people, which are so easily dismissed because they are often largely out of view.

***

For more information, including an analysis of Supreme Court rulings related to prison journalism, our full table of state restrictions, and more, see the full version of this briefing on our website [[link removed]].

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Mail scanning: A harsh and exploitative new trend in prisons [[link removed]]

Postail mail is a critical way that incarcerated people and their loved ones stay connected. But recently, prisons have implemented policies to make it harder to send and receive cards, letters, and other correspondence.

In this 2022 briefing [[link removed]], we looked at the growing trend of prison mail scanning and found that at least 14 states have adopted this misguided technology.

Unhoused and under arrest: How Atlanta polices poverty [[link removed]]

As Atlanta debates the future of policing in the city, a new dataset gives a rare look into its approach to poverty and homelessness.

In this new briefing [[link removed]], we examine data collected by the Atlanta Community Support Project. It shows that 1 in 8 city jail bookings involve a person experiencing homelessness.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor