Email

Latino Activist Rudy Lozano Was Murdered 40 Years Ago. Some Called It a ‘Political Assassination.’

| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Latino Activist Rudy Lozano Was Murdered 40 Years Ago. Some Called It a ‘Political Assassination.’ |

| Date | June 6, 2023 12:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

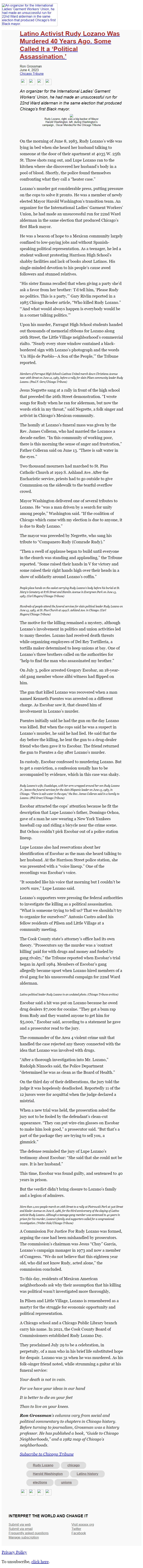

[An organizer for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’

Union, he had made an unsuccessful run for 22nd Ward alderman in the

same election that produced Chicago’s first Black mayor. ]

[[link removed]]

LATINO ACTIVIST RUDY LOZANO WAS MURDERED 40 YEARS AGO. SOME CALLED IT

A ‘POLITICAL ASSASSINATION.’

[[link removed]]

Ron Grossman

June 4, 2023

Chicago Tribune

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ An organizer for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’

Union, he had made an unsuccessful run for 22nd Ward alderman in the

same election that produced Chicago’s first Black mayor. _

Rudy Lozano, right, was a big backer of Mayor Harold Washington,

left, during Washington’s campaign., Oscar Mendez/for the Chicago

Tribune

On the morning of June 8, 1983, Rudy Lozano’s wife was lying in bed

when she heard her husband talking to someone at the door of their

apartment at 4035 W. 25th St. Three shots rang out, and Lupe Lozano

ran to the kitchen where she discovered her husband’s body in a pool

of blood. Shortly, the police found themselves confronting what they

call a “heater case.”

Lozano’s murder got considerable press, putting pressure on the cops

to solve it pronto. He was a member of newly elected Mayor Harold

Washington’s transition team. An organizer for the International

Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, he had made an unsuccessful run

for 22nd Ward alderman in the same election that produced Chicago’s

first Black mayor.

He was a beacon of hope to a Mexican community largely confined to

low-paying jobs and without Spanish-speaking political representation.

As a teenager, he led a student walkout protesting Harrison High

School’s shabby facilities and lack of books about Latinos. His

single-minded devotion to his people’s cause awed followers and

stunned relatives.

“His sister Emma recalled that when giving a party she’d ask a

favor from her brother: ‘I’d tell him, ‘Please Rudy no politics.

This is a party,’” Gary Rivlin reported in a 1985 Chicago Reader

article, “Who killed Rudy Lozano.” “‘And what would always

happen is everybody would be in a corner talking politics.’”

Upon his murder, Farragut High School students handed out thousands of

memorial ribbons for Lozano along 26th Street, the Little Village

neighborhood’s commercial rialto. “Nearly every store window

contained a black-bordered sign with Lozano’s photograph and the

words ‘Un Hijo de Pueblo—A Son of the People,’” the Tribune

reported.

Members of Farragut High School’s Latinos United march down

Christiana Avenue near 26th Street on June 12, 1983, before a rally

for slain Pilsen community leader Rudy Lozano. (Paul F. Gero/Chicago

Tribune)

Jesus Negrette sang at a rally in front of the high school that

preceded the 26th Street demonstration. “I wrote songs for Rudy when

he ran for alderman, but now the words stick in my throat,” said

Negrette, a folk singer and activist in Chicago’s Mexican community.

The homily at Lozano’s funeral mass was given by the Rev. James

Colleran, who had married the Lozanos a decade earlier. “In this

community of working poor, there is this morning the sense of anger

and frustration,” Father Colleran said on June 13. “There is salt

water in the eyes.”

Two thousand mourners had marched to St. Pius Catholic Church at 1919

S. Ashland Ave. After the Eucharistic service, priests had to go

outside to give Communion on the sidewalk to the tearful overflow

crowd.

Mayor Washington delivered one of several tributes to Lozano. He

“was a man driven by a search for unity among people,” Washington

said. “If the coalition of Chicago which came with my election is

due to anyone, it is due to Rudy Lozano.”

The mayor was preceded by Negrette, who sang his tribute to

“Companero Rudy (Comrade Rudy).”

“Then a swell of applause began to build until everyone in the

church was standing and applauding,” the Tribune reported. “Some

raised their hands in V for victory and some raised their right hands

high over their heads in a show of solidarity around Lozano’s

coffin.”

People place hands on the casket carrying Rudy Lozano's body before

his burial at St. Mary’s Cemetery at 87th Street and Hamlin Avenue

in Evergreen Park on June 13, 1983. (Carl Hugare/Chicago Tribune)

Hundreds of people attend the funeral services for slain political

leader Rudy Lozano on June 13, 1983, at St. Pius Church at 1919 S.

Ashland Ave. in Chicago. (Carl Hugare/Chicago Tribune)

The motive for the killing remained a mystery, although Lozano’s

involvement in politics and union activities led to many theories.

Lozano had received death threats while organizing employees of Del

Rey Tortilleria, a tortilla maker determined to keep unions at bay.

One of Lozano’s three brothers called on the authorities for “help

to find the man who assassinated my brother.”

On July 3, police arrested Gregory Escobar, an 18-year-old gang member

whose alibi witness had flipped on him.

The gun that killed Lozano was recovered when a man named Kenneth

Fuentes was arrested on a different charge. As Escobar saw it, that

cleared him of involvement in Lozano’s murder.

Fuentes initially said he had the gun on the day Lozano was killed.

But when the cops said he was a suspect in Lozano’s murder, he said

he had lied. He said that the day before the killing, he lent the gun

to a drug-dealer friend who then gave it to Escobar. The friend

returned the gun to Fuentes a day after Lozano’s murder.

In custody, Escobar confessed to murdering Lozano. But to get a

conviction, a confession usually has to be accompanied by evidence,

which in this case was shaky.

Rudy Lozano’s wife, Guadalupe, with her arm wrapped around her son

Rudy Lozano Jr., leaves the funeral services for the slain Hispanic

leader on June 13, 1983, in Chicago. “There is salt water in the

eyes,” the Rev. James Colleran said in a homily to Lozano. (Phil

Greer/Chicago Tribune)

Escobar attracted the cops’ attention because he fit the description

that Lupe Lozano’s father, Domingo Ochoa, gave of a man he saw

wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap and riding a bicycle near the

crime scene. But Ochoa couldn’t pick Escobar out of a police station

lineup.

Lupe Lozano also had reservations about her identification of Escobar

as the man she heard talking to her husband. At the Harrison Street

police station, she was presented with a “voice lineup.” One of

the recordings was Escobar’s voice.

“It sounded like his voice that morning but I couldn’t be 100%

sure,” Lupe Lozano said.

Lozano’s supporters were pressing the federal authorities to

investigate the killing as a political assassination. “What is

someone trying to tell us? That we shouldn’t try to organize for

ourselves?” Antonio Castro asked his fellow residents of Pilsen and

Little Village at a community meeting.

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office had its own theory.

“Prosecutors say the murder was a ‘contract killing’ paid for

with drugs and money and fueled by gang rivalry,” the Tribune

reported when Escobar’s trial began in April 1984. Members of

Escobar’s gang allegedly became upset when Lozano hired members of a

rival gang for his unsuccessful campaign for 22nd Ward alderman.

Latino political leader Rudy Lozano in an undated photo. (Chicago

Tribune archive)

Escobar said a hit was put on Lozano because he owed drug dealers

$7,000 for cocaine. “They got a bum rap from Rudy and they wanted

anyone to get him for $5,000,” Escobar said, according to a

statement he gave and a prosecutor read to the jury.

The commander of the Area 4 violent crime unit that handled the case

rejected any theory connected with the idea that Lozano was involved

with drugs.

“After a thorough investigation into Mr. Lozano,” Rudolph Nimocks

said, the Police Department “determined he was as clean as the Board

of Health.”

On the third day of their deliberations, the jury told the judge it

was hopelessly deadlocked. Reportedly 11 of the 12 jurors were for

acquittal when the judge declared a mistrial.

When a new trial was held, the prosecution asked the jury not to be

fooled by the defendant’s clean-cut appearance. “They can put

wire-rim glasses on Escobar to make him look good,” a prosecutor

said. “But that’s a part of the package they are trying to sell

you, a gimmick.”

The defense reminded the jury of Lupe Lozano’s testimony about

Escobar: “She said that she could not be sure. It is her husband.”

This time, Escobar was found guilty, and sentenced to 40 years in

prison.

But the verdict didn’t bring closure to Lozano’s family and a

legion of admirers.

More than 1,000 people march on 26th Street to a rally at Piotrowski

Park at 31st Street and Keeler Avenue on June 8, 1986, for the third

anniversary of the slaying of Latino activist Rudy Lozano. Although a

teenage gang member was sentenced to 40 years in prison for his

murder, Lozano’s family and supporters called for a congressional

investigation. (Walter Kale/Chicago Tribune)

A Commission For Justice For Rudy Lozano was formed, arguing the case

had been mishandled by prosecutors. The commission’s chairman was

Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Lozano’s campaign manager in 1973 and now a

member of Congress. “We do not believe that this eighteen year old,

who did not know Rudy, acted alone,” the commission concluded.

To this day, residents of Mexican American neighborhoods ask why their

assumption that his killing was political wasn’t investigated more

thoroughly,

In Pilsen and Little Village, Lozano is remembered as a martyr for the

struggle for economic opportunity and political representation.

A Chicago school and a Chicago Public Library branch carry his name.

In 2021, the Cook County Board of Commissioners established Rudy

Lozano Day.

They proclaimed July 29 to be a celebration, in perpetuity, of a man

who in his brief life substituted hope for despair. Lozano was 31 when

he was murdered. As his folk-singer friend noted, while strumming a

guitar at his funeral service:

_Your death is not in vain._

_For we have your ideas in our hand_

_It is better to die on your feet_

_Than to live on your knees._

_RON GROSSMAN's columns vary from social and political commentary to

chapters in Chicago history. Before turning to journalism, Grossman

was a history professor. He has published a book, “Guide to Chicago

Neighborhoods,” and a 1982 map of Chicago's neighborhoods._

_Subscribe to Chicago Tribune

[[link removed]]_

* Rudy Lozano

[[link removed]]

* chicago

[[link removed]]

* Harold Washington

[[link removed]]

* Latino history

[[link removed]]

* elections

[[link removed]]

* unions

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Union, he had made an unsuccessful run for 22nd Ward alderman in the

same election that produced Chicago’s first Black mayor. ]

[[link removed]]

LATINO ACTIVIST RUDY LOZANO WAS MURDERED 40 YEARS AGO. SOME CALLED IT

A ‘POLITICAL ASSASSINATION.’

[[link removed]]

Ron Grossman

June 4, 2023

Chicago Tribune

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ An organizer for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’

Union, he had made an unsuccessful run for 22nd Ward alderman in the

same election that produced Chicago’s first Black mayor. _

Rudy Lozano, right, was a big backer of Mayor Harold Washington,

left, during Washington’s campaign., Oscar Mendez/for the Chicago

Tribune

On the morning of June 8, 1983, Rudy Lozano’s wife was lying in bed

when she heard her husband talking to someone at the door of their

apartment at 4035 W. 25th St. Three shots rang out, and Lupe Lozano

ran to the kitchen where she discovered her husband’s body in a pool

of blood. Shortly, the police found themselves confronting what they

call a “heater case.”

Lozano’s murder got considerable press, putting pressure on the cops

to solve it pronto. He was a member of newly elected Mayor Harold

Washington’s transition team. An organizer for the International

Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, he had made an unsuccessful run

for 22nd Ward alderman in the same election that produced Chicago’s

first Black mayor.

He was a beacon of hope to a Mexican community largely confined to

low-paying jobs and without Spanish-speaking political representation.

As a teenager, he led a student walkout protesting Harrison High

School’s shabby facilities and lack of books about Latinos. His

single-minded devotion to his people’s cause awed followers and

stunned relatives.

“His sister Emma recalled that when giving a party she’d ask a

favor from her brother: ‘I’d tell him, ‘Please Rudy no politics.

This is a party,’” Gary Rivlin reported in a 1985 Chicago Reader

article, “Who killed Rudy Lozano.” “‘And what would always

happen is everybody would be in a corner talking politics.’”

Upon his murder, Farragut High School students handed out thousands of

memorial ribbons for Lozano along 26th Street, the Little Village

neighborhood’s commercial rialto. “Nearly every store window

contained a black-bordered sign with Lozano’s photograph and the

words ‘Un Hijo de Pueblo—A Son of the People,’” the Tribune

reported.

Members of Farragut High School’s Latinos United march down

Christiana Avenue near 26th Street on June 12, 1983, before a rally

for slain Pilsen community leader Rudy Lozano. (Paul F. Gero/Chicago

Tribune)

Jesus Negrette sang at a rally in front of the high school that

preceded the 26th Street demonstration. “I wrote songs for Rudy when

he ran for alderman, but now the words stick in my throat,” said

Negrette, a folk singer and activist in Chicago’s Mexican community.

The homily at Lozano’s funeral mass was given by the Rev. James

Colleran, who had married the Lozanos a decade earlier. “In this

community of working poor, there is this morning the sense of anger

and frustration,” Father Colleran said on June 13. “There is salt

water in the eyes.”

Two thousand mourners had marched to St. Pius Catholic Church at 1919

S. Ashland Ave. After the Eucharistic service, priests had to go

outside to give Communion on the sidewalk to the tearful overflow

crowd.

Mayor Washington delivered one of several tributes to Lozano. He

“was a man driven by a search for unity among people,” Washington

said. “If the coalition of Chicago which came with my election is

due to anyone, it is due to Rudy Lozano.”

The mayor was preceded by Negrette, who sang his tribute to

“Companero Rudy (Comrade Rudy).”

“Then a swell of applause began to build until everyone in the

church was standing and applauding,” the Tribune reported. “Some

raised their hands in V for victory and some raised their right hands

high over their heads in a show of solidarity around Lozano’s

coffin.”

People place hands on the casket carrying Rudy Lozano's body before

his burial at St. Mary’s Cemetery at 87th Street and Hamlin Avenue

in Evergreen Park on June 13, 1983. (Carl Hugare/Chicago Tribune)

Hundreds of people attend the funeral services for slain political

leader Rudy Lozano on June 13, 1983, at St. Pius Church at 1919 S.

Ashland Ave. in Chicago. (Carl Hugare/Chicago Tribune)

The motive for the killing remained a mystery, although Lozano’s

involvement in politics and union activities led to many theories.

Lozano had received death threats while organizing employees of Del

Rey Tortilleria, a tortilla maker determined to keep unions at bay.

One of Lozano’s three brothers called on the authorities for “help

to find the man who assassinated my brother.”

On July 3, police arrested Gregory Escobar, an 18-year-old gang member

whose alibi witness had flipped on him.

The gun that killed Lozano was recovered when a man named Kenneth

Fuentes was arrested on a different charge. As Escobar saw it, that

cleared him of involvement in Lozano’s murder.

Fuentes initially said he had the gun on the day Lozano was killed.

But when the cops said he was a suspect in Lozano’s murder, he said

he had lied. He said that the day before the killing, he lent the gun

to a drug-dealer friend who then gave it to Escobar. The friend

returned the gun to Fuentes a day after Lozano’s murder.

In custody, Escobar confessed to murdering Lozano. But to get a

conviction, a confession usually has to be accompanied by evidence,

which in this case was shaky.

Rudy Lozano’s wife, Guadalupe, with her arm wrapped around her son

Rudy Lozano Jr., leaves the funeral services for the slain Hispanic

leader on June 13, 1983, in Chicago. “There is salt water in the

eyes,” the Rev. James Colleran said in a homily to Lozano. (Phil

Greer/Chicago Tribune)

Escobar attracted the cops’ attention because he fit the description

that Lupe Lozano’s father, Domingo Ochoa, gave of a man he saw

wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap and riding a bicycle near the

crime scene. But Ochoa couldn’t pick Escobar out of a police station

lineup.

Lupe Lozano also had reservations about her identification of Escobar

as the man she heard talking to her husband. At the Harrison Street

police station, she was presented with a “voice lineup.” One of

the recordings was Escobar’s voice.

“It sounded like his voice that morning but I couldn’t be 100%

sure,” Lupe Lozano said.

Lozano’s supporters were pressing the federal authorities to

investigate the killing as a political assassination. “What is

someone trying to tell us? That we shouldn’t try to organize for

ourselves?” Antonio Castro asked his fellow residents of Pilsen and

Little Village at a community meeting.

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office had its own theory.

“Prosecutors say the murder was a ‘contract killing’ paid for

with drugs and money and fueled by gang rivalry,” the Tribune

reported when Escobar’s trial began in April 1984. Members of

Escobar’s gang allegedly became upset when Lozano hired members of a

rival gang for his unsuccessful campaign for 22nd Ward alderman.

Latino political leader Rudy Lozano in an undated photo. (Chicago

Tribune archive)

Escobar said a hit was put on Lozano because he owed drug dealers

$7,000 for cocaine. “They got a bum rap from Rudy and they wanted

anyone to get him for $5,000,” Escobar said, according to a

statement he gave and a prosecutor read to the jury.

The commander of the Area 4 violent crime unit that handled the case

rejected any theory connected with the idea that Lozano was involved

with drugs.

“After a thorough investigation into Mr. Lozano,” Rudolph Nimocks

said, the Police Department “determined he was as clean as the Board

of Health.”

On the third day of their deliberations, the jury told the judge it

was hopelessly deadlocked. Reportedly 11 of the 12 jurors were for

acquittal when the judge declared a mistrial.

When a new trial was held, the prosecution asked the jury not to be

fooled by the defendant’s clean-cut appearance. “They can put

wire-rim glasses on Escobar to make him look good,” a prosecutor

said. “But that’s a part of the package they are trying to sell

you, a gimmick.”

The defense reminded the jury of Lupe Lozano’s testimony about

Escobar: “She said that she could not be sure. It is her husband.”

This time, Escobar was found guilty, and sentenced to 40 years in

prison.

But the verdict didn’t bring closure to Lozano’s family and a

legion of admirers.

More than 1,000 people march on 26th Street to a rally at Piotrowski

Park at 31st Street and Keeler Avenue on June 8, 1986, for the third

anniversary of the slaying of Latino activist Rudy Lozano. Although a

teenage gang member was sentenced to 40 years in prison for his

murder, Lozano’s family and supporters called for a congressional

investigation. (Walter Kale/Chicago Tribune)

A Commission For Justice For Rudy Lozano was formed, arguing the case

had been mishandled by prosecutors. The commission’s chairman was

Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Lozano’s campaign manager in 1973 and now a

member of Congress. “We do not believe that this eighteen year old,

who did not know Rudy, acted alone,” the commission concluded.

To this day, residents of Mexican American neighborhoods ask why their

assumption that his killing was political wasn’t investigated more

thoroughly,

In Pilsen and Little Village, Lozano is remembered as a martyr for the

struggle for economic opportunity and political representation.

A Chicago school and a Chicago Public Library branch carry his name.

In 2021, the Cook County Board of Commissioners established Rudy

Lozano Day.

They proclaimed July 29 to be a celebration, in perpetuity, of a man

who in his brief life substituted hope for despair. Lozano was 31 when

he was murdered. As his folk-singer friend noted, while strumming a

guitar at his funeral service:

_Your death is not in vain._

_For we have your ideas in our hand_

_It is better to die on your feet_

_Than to live on your knees._

_RON GROSSMAN's columns vary from social and political commentary to

chapters in Chicago history. Before turning to journalism, Grossman

was a history professor. He has published a book, “Guide to Chicago

Neighborhoods,” and a 1982 map of Chicago's neighborhoods._

_Subscribe to Chicago Tribune

[[link removed]]_

* Rudy Lozano

[[link removed]]

* chicago

[[link removed]]

* Harold Washington

[[link removed]]

* Latino history

[[link removed]]

* elections

[[link removed]]

* unions

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV