|

How a Baby Pig Broke Big Ag’s Doom Loop

Lily the pig passed away last week. But her legacy has the power to break humanity’s most ancient cycle of violence.

What’s up this week:

Fighting the doom loop. Our civilization is facing a vicious cycle of violence that may lead to its demise. But the life of one baby pig shows us how to break out of the cycle. I explain more below, in a celebration of Lily, who passed away last week. But two things are key: fight and hope.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Prop 12 this week, in defense of mother pigs. Newsweek has one of the most interesting write-ups, including the hysterical reaction by certain Republican members of Congress. I’ll have more to say about this, but perhaps the most interesting thing to note about Justice Gorsuch’s opinion is that it highlights the corrupt and anti-democratic nature of Big Pork’s effort to repeal Prop 12.¹ When even the Court’s most conservative justice recognizes that the public is against you, the writing is on the wall.

Science Magazine, the most important research publication in the world, released a study this week showing that early hominids depended on plants, not meat, to allow their large brains to grow. The research, which looked at bacterial DNA on the fossils of Neanderthals, found compelling evidence that early hominids relied on high carbohydrate foods to fuel their development. This contradicts many popular narratives about the evolutionary necessity of meat.

Peter Singer is touring the country. It is nearing the 50 year anniversary of the publication of Animal Liberation, and this tour will be a part of animal rights history. I’ll be blogging more about this next week, but you really do not want to miss this tour. I may be able to give readers of this Substack a discount. Stay tuned!

We’re still looking for a video editor! Here is a job description. Send us a note if you know anyone who might be a good fit.

Fighting the Doom Loop

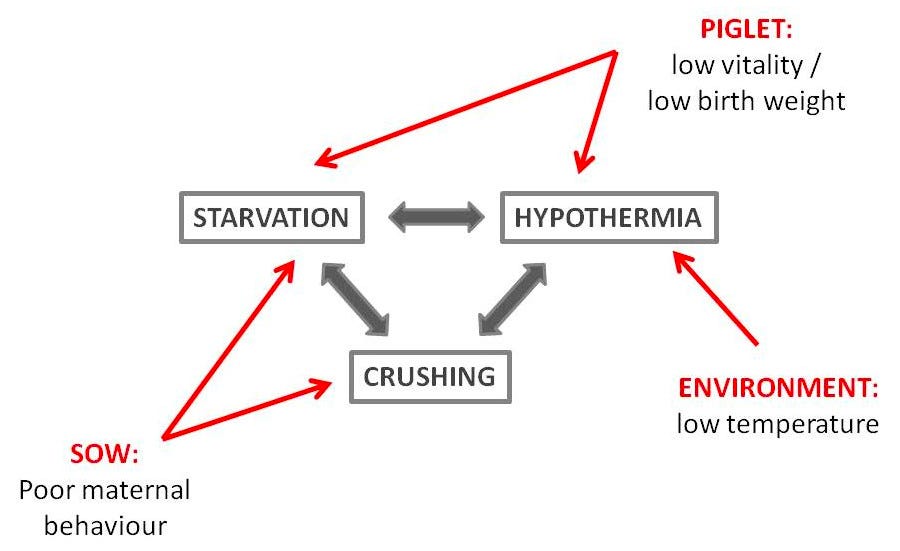

There is a haunting scene that unfolds over and over again in factory farms across the nation. A small animal, typically born just a few days or weeks ago, is struggling to reach food or water. While birds or mammals in a natural setting will cry out for their moms for help, in factory farms, the moms are missing, or trapped in a cage. And so this tiny creature, like billions before her, will slowly starve to death — a victim of the industry’s relentless pursuit of profit. Indeed, the pig farming industry has a name for this process: the hypothermia-starvation-crushing (HSC) complex.

Here is how the complex works: Baby pigs who are denied access to their mother’s warmth suffer from the unnatural cold. Weakness caused by the cold, in turn, makes it difficult for the babies to reach food and water, causing them to starve. Finally, cold and malnourished piglets are easily crushed under piles of other pigs, as they lose the ability to struggle or escape the weight of the throngs of animals around them. The HSC complex is an example of a doom loop: a vicious cycle of suffering that feeds on itself.

In pig farms, the doom loop is replayed upwards of 20 million times every year in the United States, as baby pigs starve or are crushed by the HSC complex. In dairy farms, the number is 2-3 million, with digestive disease and subsequent dehydration being the primary drivers of demise. And on poultry farms, 300-400 million animals die in doom loops triggered by lameness, cardiac disease, and a genetically-modified rate of growth.

But it is not just animals who are endangered by Big Ag’s doom loop. As I’ve previously argued, Big Ag threatens us all. This is because the system of industrial agriculture prioritizes the artificial goals of non-sentient entities — e.g., the profit motive of the modern corporation — over values that actually matter, such as joy or suffering. The fact that leading climate researchers now say it will be “impossible” to contain climate change without transitioning towards a plant-based diet is one example. The growing concern over pandemics 20+ times as devastating as COVID-19, born from factory farms, is another. Each new manure lagoon makes the last one even more dangerous. Each new pathogenic outbreak is more deadly than the last — driven by mutation and drug resistance.

There is, however, a solution to this vicious cycle. And we can see that solution in the story of that piglet who survived.

How Lily Found Her Way Out

In March 2017, I saw Lily in a farrowing crate, caught in a doom loop. She was struggling to walk, with a golf-ball sized infected lesion on her foot. She was emaciated, perhaps one-fourth the size of the other piglets. And every time she tried to move, much less reach her mother’s milk, she was crushed by a throng of other pigs.

Things were so bad that, when I first saw her, my reaction was to look away.

“She’s not going to make it out. There’s no point in even thinking about it,” I said to myself. We make difficult decisions as open rescue activists, including which dying animals to leave behind. Initially, Lily was in that group, one of the 20 million piglets who would not make it out of the nursery alive.

But every time I looked back, I noticed something unusual. Lily, despite impossible odds, continued to try. She would cry and sometimes fall to the metal floor when she was tossed aside by the larger animals in her cage. But she would get right back up, and try again, pushing her tiny little nose towards an udder, balancing on one foot to avoid the debilitating pain from her injured back leg. I never saw her successfully nurse. She was far too small to get through the crowd to food. But it did not stop her from trying, time and time again. And after perhaps a dozen failed tries, she looked up at me, this human giant towering over her farrowing cage, and I knew the look in her eyes.

“I’m willing to fight,” she said with her eyes.

I felt a tear forming in my eyes, as I imagined Lily’s life if I left her behind. Every day would get worse. The inflammation in her foot would only grow. Her weakness would eventually turn into complete immobility, as she collapsed on the floor, starving. If she was lucky, a human worker would come by and smash her skull against the concrete. More likely, she would slowly starve or be crushed to death.

She looked up at me again. Her eyes were telling me, “I’m willing to fight. But I need your help.”

I told the team we were taking her, even though I expected her to die.

There was something else unusual about this baby pig, however, that we quickly recognized when we took her back to sanctuary. Most piglets cry and scream at being handled by human beings. Unlike kittens or puppies, they are not accustomed to being carried or given medical treatment or even touched. Indeed, many piglets are terrified by human beings, as everything they’ve seen from humans has been violence.

But Lily was different. Despite being in incredible pain, she allowed us to dip her foot into a stinging antibiotic wash. Despite the fear of a completely new environment, she calmed down and eventually began to sleep and eat. And despite knowing nothing but cruelty at human hands, she trusted me enough to sleep on my chest, borrowing from my warmth when she was cold in the night.

She had a powerful sense of hope, even when facing impossible odds. And her goodwill towards the world, and those around her, allowed her to calm the stress and nerves and get needed sleep. It allowed her to accept the medication and treatment she would need to get through her emergency medical condition. And it allowed her to trust the people she needed to trust to find a better life.

There’s a lesson in Lily’s story for all of us. When we are trapped in a doom loop — individually or collectively, as a species — there is a way out. But it requires us to fight, even when things are hard. And to hope, even when things are dark.

These very attributes not only helped Lily survive. They inspired a generation of activists and animal lovers who met Lily at Luvin Arms in Colorado. She was, through her 7 years of life, the star of the sanctuary because of her fight, and her hope.

How We Can Escape the Doom Loop, Too

The world is in a very difficult place. And it’s natural for people to live their lives afraid. This is especially true of the younger generations who, for the first time in American history, may have a bleaker future than their ancestors. One recent survey shows a shocking drop, in recent decades, in the percentage of young people who are willing to take risks.

But this is exactly the wrong lesson. If we want to escape the cycles of negativity and suffering — the doom loop — we need to take more risks, not fewer. We have to be willing to fight.

Fighting, however, is not enough. If we fight with the wrong attitude, it may very well be counterproductive. Ezra Klein, among many others, has shown how the extreme polarization of America prevents social change and makes individual citizens scared and miserable. We need to fight, but we need to do so with hope in our hearts.

And yet the modern culture of both the left and the right, especially in activist circles, is one of anxiety and despair rather than optimism for change. This comes despite an incredible number of positive signs. In the fight to save life on this earth, movements have never been stronger. People laughed about climate change and species loss two decades ago. (I know this, because they laughed at my my paper, published in 2007.) Now it is an international priority.

But somehow, our very strength — at provoking awareness, discussion, and change — has become a reason for despair. We need to change this dynamic if we hope to escape the doom loop. Knowing there are problems, even urgent and devastating ones, is the first step to finding solutions. And the fact that our society has reached that point of awareness on so many issues — housing, climate change, and eventually, animal rights — is a step on the path to progress.

Lily’s life shows this. It was impossible for any of us, least of all Lily, to ignore the dire situation she was in. But it was precisely because we recognized the emergency — but also had the confidence to act — that she was able to escape the doom loop and live a long and beautiful life.

All of us can do the same. All it takes is fight and hope.

For those of you who want to honor Lily’s memory, please consider making a donation to Luvin Arms sanctuary, which gave Lily an incredible life for 6 years. Luvin Arms, like many sanctuaries, has faced serious obstacles due to the pandemic, and new fundraising sources are crucial to sustaining their life-saving work. I am making a $100 donation to the sanctuary myself. I hope you’ll consider matching that contribution, or giving whatever you can. Every bit helps.

A choice excerpt (emphasis added):

If, as petitioners insist, California’s law really does threaten a “massive” disruption of the pork industry, see Brief for Petitioners 2, 4, 19—if pig husbandry really does “‘imperatively demand’” a single uniform nationwide rule, id., at 27—they are free to petition Congress to intervene. Under the (wakeful) Commerce Clause, that body enjoys the power to adopt federal legislation that may preempt conflicting state laws. That body is better equipped than this Court to identify and assess all the pertinent economic and political interests at play across the country. And that body is certainly better positioned to claim democratic support for any policy choice it may make. But so far, Congress has declined the producers’ sustained entreaties for new legislation. See Part I, supra (citing failed efforts). And with that history in mind, it is hard not to wonder whether petitioners have ventured here only because winning a majority of a handful of judges may seem easier than marshaling a majority of elected representatives across the street.

The Simple Heart is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, you can tell The Simple Heart that their writing is valuable by pledging a future subscription. You won't be charged unless they enable payments.