|

The Moral Panic Over Animal Rescue

From the Salem Witch Trials to the Red Scare, moral panics have ruined lives and set our nation adrift. Now they’re coming for animal rights advocates.

What’s Up This Week

The moral panic over animal rescue is spreading across the country – and leading to threats of prosecution and violence against animal advocates, including the conviction of Curtis Vollmar this week in Beaver, Utah. I explain why it’s happening, and how we can fight back, in the below newsletter. I’ll also be going live on Friday at 10:30 am to discuss.

Philosopher Peter Singer had a powerful op-ed in the New York Times this week on how fixing our diet can save the planet. Check it out, and don’t forget that Peter is touring the country (including SF on May 30) to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Animal Liberation.

The Animal Liberation Conference is right around the corner, from June 9-14. This is, in my view, the biggest animal rights event of the year. Don’t miss it.

The Simple Heart is looking to hire a video editor to tell the story of open rescue! Video is the name of the game in today’s media climate, and we need someone with experience and passion to seize the opportunity. Here is a job description. Send us a note if you know anyone who might be a good fit.

—

Moral Panics and Animal Rights

On April 25th, a court in Beaver, Utah convicted my friend Curtis Vollmar of disorderly conduct and trespass for peacefully leafleting on a public sidewalk. In separate legal proceedings related to Curtis’s case, the government submitted a declaration by a witness, Chris Eyre, who stated, under penalty of perjury, that “these men were environmental terrorist [sic],” that “being approached by this terrorist totally ruined my day,” and that Eyre’s wife “was afraid I was going to hit him.”

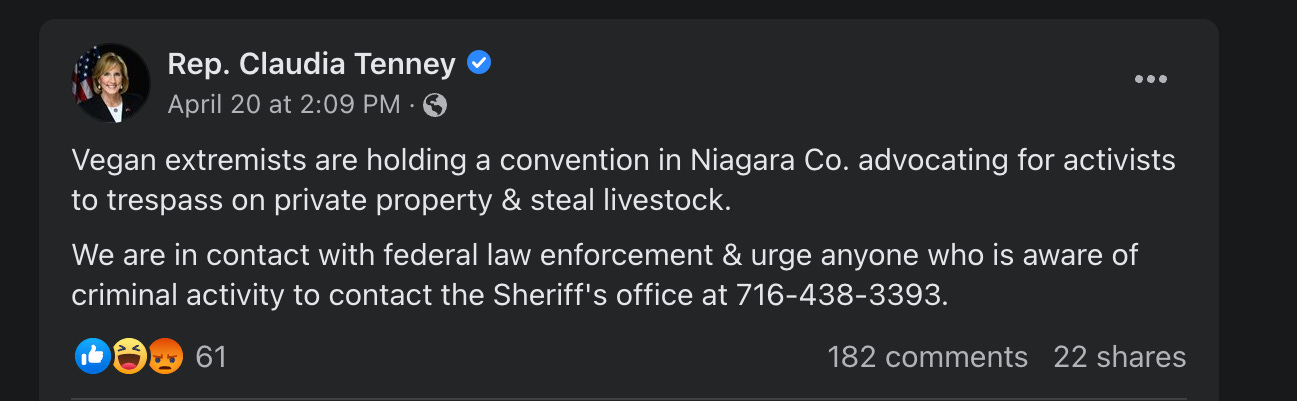

Across the country, a US House member – one of the 435 members of the legislature that writes all the laws for our nation – posted last week that “vegan extremists are holding a convention” and stated that she was in “contact with federal law enforcement” about her concern.

The main subject of the “convention”? How to care for sick and injured animals. Tracy Murphy shared stories of caring for a baby cow, Darsha, who was abandoned because she was born without working eyes, and therefore struggled to reach food and water. Bringing this poor baby back to life apparently was, to Rep. Claudia Tenney, a subject for federal law enforcement to investigate.

Each of these cases, however, is not just an isolated instance of our legal and political institutions becoming deeply weird (and wrong). They are evidence of a broader moral panic in rural America about animal rights. Moral panics have occurred through human history: the Salem witch trials in the late 17th century, in which innocent people were accused of being wizards and witches and summarily executed for their “crimes”; the Red Scare in the mid 20th Century, where thousands of Americans were imprisoned or fired based on the faintest allegations of Communist affiliation; and, more recently, conspiracy theories such as QAnon, which have bizarrely inspired thousands of Americans to protest and even riot to prevent Satanic forces from taking over the country.

Moral panics, however, should not just be a concern for those targeted by their false allegations. They affect the civil liberties of all Americans, including our First (speech) and Fourteenth (privacy) Amendment rights.

Take the First Amendment issues in Curtis’s recent trial. Witnesses described his outreach as “pleasant,” “cordial,” and “not unruly.” There was not even a word of testimony at his trial suggesting that Curtis blocked pedestrian traffic or disobeyed an officer’s lawful order, the legal standard required for disorderly conduct in Utah. The only officer to testify, Deputy Tyler Schena, said that Curtis was friendly and that he “absolutely” complied with all law enforcement orders. But the mass hysteria in Beaver County about animal advocates was enough to make his friendly outreach a criminal or even terrorist act – and his conviction proves that the panic crept into our legal system. That is a violation of the First Amendment, which guarantees all Americans freedom of speech.

Or consider the Fourteenth Amendment issues in Tracy’s case. Rep. Tenney, and the numerous other elected officials who have spoken out against her and “vegan extremists” in upstate New York, have provided no evidence whatsoever that Tracy or any animal advocate has committed a crime. Indeed, the only evidence that Tenney and her allies have been able to obtain is the statement of a single farmer, who claims that he saw two people taking photographs outside of his farm and public storefront. Taking photos, however, is not a crime. And the call for federal law enforcement to a situation where no crime has even been alleged, is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees that no citizen is harassed, investigated, or charged by a state government without evidence of unlawful conduct.

In other words, it is not just animal advocates who should be deeply concerned about these cases. Because, if a moral panic can undermine our most basic civil liberties in one case, it will happen in others, too.

How to Stop a Moral Panic

So what can we do about these moral panics? Stanley Cohen, the groundbreaking sociologist who first identified this pattern of human behavior, gives us some ideas. He identified four key agents of moral panic that are eerily similar to the forces at play in Curtis and Tracy’s cases:

The media. Especially in the early stage of a moral panic, the media exaggerates and distorts the facts and publishes dire predictions of the failure to act. (In today’s world, social media often plays this role to an even greater degree.)

Moral entrepreneurs. Demagogues who can obtain power or wealth via a false narrative invest resources into spreading the panic.

Institutions of social control. Those with institutional credibility and power turn a media-generated mob into active legal repression.

The public. Due to false media narratives, and the endorsement by credible legal and political institutions – such as courts or elected officials – the public supports the panic, and the legal repression.

There are effective tactics, however, for overcoming each of these agents of hysteria.

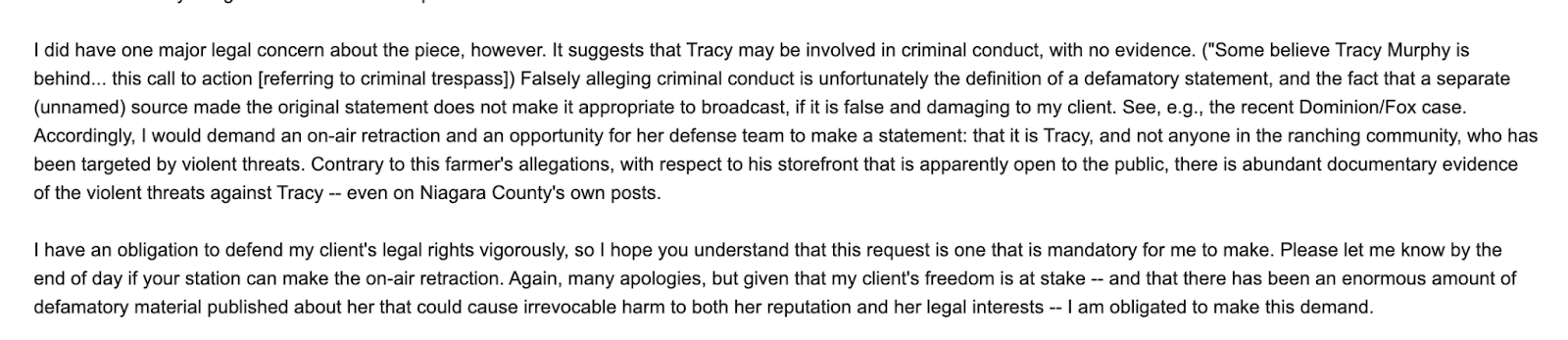

Media falsehoods must be confronted with the risk of liability. Virtually all media outlets, in today’s world, are business enterprises. The professional values of journalism have been in dramatic decline. And the only way to get the media’s attention, when they can make money off a false narrative, is to show them that they will lose more money than they will make by spreading the panic. The story of Fox News and Dominion voting is one that virtually all journalists will know. And at DxE, we have obtained retractions and corrections in a number of media articles that spread false narratives in the last ten years. In one case, the threat of liability even caused a tabloid to kill a fabricated story. While it’s best if a lawyer sets out the case for liability against a media outlet, even ordinary citizens can issue a demand for a retraction and warn a media outlet that it faces liability. Here’s an example from an email I sent to one media outlet about Tracy’s case.

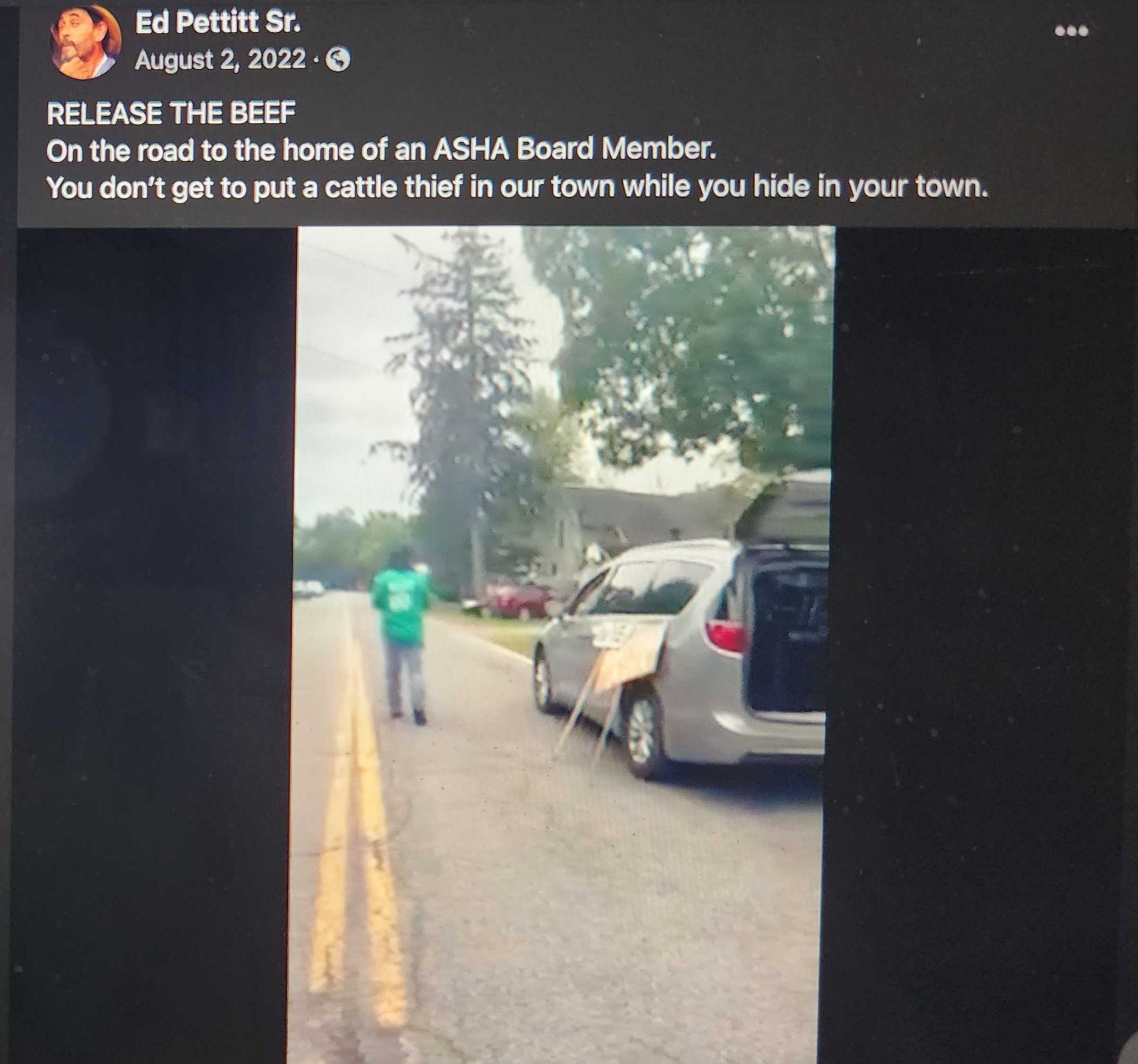

Moral entrepreneurs who are inspiring a mob must be challenged with transparency. When people see that they are motivated by influence or profit, and not genuine community concerns, their power can quickly evaporate. Ed Pettitt Sr., a moral entrepreneur who has been feeding the mob against Tracy Murphy, is one such example. In engaging with him, I have tried to calmly point out that the threats that he suggests are without evidence, and that, in contrast, the harms caused by his actions (e.g., death threats against Tracy, mobs gathering outside of her home) are quite real. It takes some bravery to go up against such demagogues with facts, because moral entrepreneurs are prone to personal attacks and layering additional falsehoods on their original lies. But when people do begin standing up to them, with the power of transparency, their power is greatly diminished.

Institutions of social control that persecute the victims of a moral panic must face mockery. Unlike the media, these institutions aren’t motivated by profit. Key decision-makers within the institution, unlike moral entrepreneurs, may not see the panic as a source of influence or profit but rather as a way to ensure they themselves are not targeted by the media or moral entrepreneurs. In short, they are motivated to persecute and prosecute in order to maintain their reputation. And the best way to undermine this motivation is to show that their reputations will be even more greatly tarnished by feeding into the moral panic. Glenn Greenwald’s mockery of the FBI for chasing baby piglets in the Smithfield case, for example, was probably crucial in preventing a federal prosecution. And the many activists on Rep. Claudia Tenney’s facebook page, poking fun at her for focusing on “vegan extremism” when the nation is in economic and social crisis, are helping to ensure the panic stops before real persecution begins.

Finally, the antidote to a public that has been deceived by a moral panic is better deliberation. Moral panics rely on emotion and quick judgment. They count on a public, terrified by false and exaggerated accounts of threat, not being able to carefully review the evidence or reason behind an allegation. That is precisely why we have to seek this careful review of evidence and reason when a moral panic is rising, so the public is getting more than just a soundbite. The jury system is one such antidote. Even in Southern Utah, when a jury of 8 citizens was given the time and instruction to deliberate carefully in an actual case of animal rescue, they got to the right answer: animal rescuers and advocates are caretakers, not terrorists.

We have to seek the same deliberative outcome in other contexts where a moral panic is unfolding. This is why I’ve asked Ed Pettitt Sr., one of the main moral entrepreneurs behind the New York moral panic, to have a published long-form conversation about his concerns. It’s why I am writing this very piece; fair people on all sides will read it, I hope, and realize the lack of evidence and reason behind the allegations of “vegan extremism.” And it is why, in both Curtis and Tracy’s cases, I am hopeful that jury deliberation, which forces a random set of citizens to look carefully at evidence and reasons, will weaken the power of the moral panic in the public.

While these tactics are not foolproof, there is compelling evidence that they have worked in the past. For example, in response to the Red Scare, activists used a combination of transparency and mockery to finally end the mass hysteria and persecution that destroyed the lives of thousands of Americans. And the words of one of these activists, a lawyer named Joseph Welch who confronted McCarty with the power of reason and deliberation, will remain etched in history: “Have you no decency, sir?”

I will pass those same words to Claudia Tenney and Ed Pettitt, Sr: “Have you no decency?” Let’s end the threats and hysteria and start doing things the way American democracy intended for them to be done: having a conversation, and letting the people (or jury) decide.