|

Animal Liberation is Happening. The Open Rescue Trials Prove It.

The acquittal of animal rights activists in recent trials shows that change for animals is happening far faster than any of us believed. Here's why.

In this email:

The open rescue trials show that support for animal liberation is rapidly growing. The main focus of this newsletter is analyzing why that’s the case. I’ll also be going live on Friday at 10:30 am to discuss. Click here to join that livestream!

This weekend, the jurors from the Foster Farms trial will share with us why they chose to defend the right to rescue. I’ll also be doing the latest version of the Open Rescue Experience workshop. Registration has closed, but if you reply to this email, there’s a chance I can get you in!

The trial of Curtis Vollmar is happening next Tuesday, April 23, and I’ll be there. Follow my facebook page, as I’ll be giving updates on the trial, doing some vegan outreach in Sanpete, and probably organizing a hang-out on the morning of Thursday, April 25.

The father of the animal rights movement, Peter Singer, is going on tour, including SF on May 30. It’s been nearly 50 years since Singer’s Animal Liberation was published. I’ll have much more to say about this but, for now, make sure you buy tickets to Singer’s event as he tours the country.

Animal Liberation is Happening. The Open Rescue Trials Prove It.

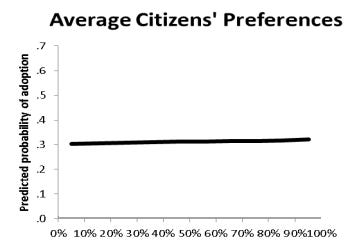

One of the great puzzles of animal rights is how there can be so little support for animal rights in people’s daily habits – rates of vegetarianism are less than 5% nationwide, and possibly declining – despite widespread condemnation of animal cruelty. For example, recent polling data shows that 80% of voters say that preventing cruelty to farm animals is a “personal moral concern.” Even more shocking, polling data by agricultural economist Bailey Norwood – who is a consultant for the livestock industry – suggests that half of Americans would support an outright ban on slaughterhouses!

How do we reconcile the data?

The answer, at least in part, is provided by the historic victories in Merced, CA, and Beaver, Utah over the last year: while most people are not vegetarian, when ordinary people are given the opportunity to deliberate, they support the liberation of animals.

But both parts of that statement – (a) ordinary people and (b) the opportunity to deliberate – are crucial.

Ordinary people, drawn randomly from the public, are much better decision-makers than elected officials or judges. They are immune from the regulatory capture and inertia that generally blocks progress on animal rights.

The opportunity to deliberate, however, is just as crucial. While ordinary people do recognize the atrocities committed against animals, they suffer from a number of logical fallacies that often prevent them from endorsing change. (Ergo, the low rates of veganism.) By providing a social context that allows people to overcome these biases – including preference falsification and strategic ignorance – the open rescue trials allow ordinary citizens to demonstrate their support for animal rights.

There is one final point that is perhaps most important, however. The open rescue trials are not just showing support for animals. They are amplifying it. The reason is that, when ordinary people make decisions, not just as private citizens but as jurors, they set an important political precedent that subsequently influences other citizens. The reason is that legal decisions, such as trial verdict, have an expressive function that can reshape public attitudes on important issues.

The open rescue trials, in short, are not just a thermometer for where the public stands on animal rights. They are an engine for change.

The perils of regulatory capture

There is widespread acceptance that our government is, in important ways, controlled by wealthy elites. One study even suggests that ordinary people have virtually no influence on government policy, as compared to the ultra-wealthy and their corporate allies. Polling data shows that a large and growing majority of Americans are concerned about corporate influence

The reason for this is rarely, at least in the United States, outright corruption. The reason, instead, is that most voters are isolated, acting with limited information, and unorganized. In contrast, corporations are organized and strategic in their efforts to change policy. The net result is that politicians who oppose the interests of ordinary voters are rarely punished. In contrast, those politicians that cross a powerful corporation in their district will rarely live to see another political day. This is why, in a shockingly candid conversation I had with elected sheriff Cameron Noel in Beaver County, I was told, “This is a Smithfield town. We do what they say.”

The result of this corporate influence is not just anti-democratic decisions but policies that are fundamentally mis-aligned with the things that matter most.

Changing these decisions and policies, in turn, is difficult because of regulatory inertia. Indeed, the American system of checks and balances was partly an effort to prevent rabble-rousing populists from enacting policies that would go against the rich and business class. Human beings are already prone to the status quo, especially in groups. When our institutions are designed to prevent change – as journalist Ezra Klein has persuasively argued, using examples such as the Senate filibuster – it becomes near impossible to enact reforms when there is a powerful interest group opposing the effort.

The beauty of the jury trial, however, is that it overcomes all these obstacles. It’s impossible for corporations to capture ordinary citizens who are randomly drawn from the public. And the inertia that normally blocks change in institutions is overcome by activists who force a legal decision by putting their own freedom on the line. The net result is that, even in a context where industry interest groups have nearly unparalleled influence, and where hundreds of years of history have prevented change, we can achieve unprecedented political victories.

Overcoming self-deception and ignorance

But it’s not just government that is changed by these cases. Public attitudes are, too. Most human beings, as social animals, will do as others do. And this is especially true when an issue is moral in nature. A human being with strange moral views is a human being who is unlikely to survive, through most of our evolutionary history, because morality is a huge part of what defines human tribal affiliation.

The result of this, however, is that people who have dissenting moral views often lie about their own views. This concept, which social scientists call preference falsification, is one of the largest obstacles for social change. Because, even if we influence people, we cannot create change if they are unwilling to even say (much less act) they have been persuaded.

This is especially true when the new moral belief we are trying to create is one that creates psychological and social costs for the person who has been changed. And accepting that crimes are being committed against animals comes at immense personal cost. The people around you suddenly go from normal and upstanding citizens to participants in an atrocity. It’s for this reason that most people choose to remain strategically ignorant. This ignorance, in turn, is one of the defining attributes of periods in history where some great moral crime is being committed.

How can we reckon with a problem if people are: (a) lying about it, even to themselves; and (b) choosing (intentionally) to be ignorant of it.

The beauty of the jury deliberation, however, is that it overcomes these problems. Citizens are no longer allowed to hide their actual views. The secret deliberation of a jury forces them to reveal their preferences. And they are not allowed to avert their eyes and remain strategically ignorant. Jurors are forced to listen to the evidence — including, in our cases, evidence of animal cruelty. And even when a judge wrongfully denies most of our evidence, we still have succeeded in getting our central narrative into court: that rescuing animals is not a crime. When jurors have heard this narrative, they are convinced.

Expanding the Overton Window

But the impacts of these trials goes far beyond the 12 jurors in a room. Legal decisions, it turns out, have huge impacts in how everyone in our society perceives the state of public attitudes on an issue. These decisions, in other words, change social norms.

The psychologist Betsy Paluck at Princeton has shown this in the context of gay rights. A single courtroom decision plausibly had greater impacts on social norms than 10 years of grassroots struggle beforehand. The reason is that, especially when citizens are falsifying their preferences, and remaining in strategic ignorance, they are dreadfully bad at perceiving how others actual feel about an issue. The public nature of a courtroom decision, when it deviates from mainstream norms, can therefore reshape public attitudes.

“Wow, I had no idea so many other people support animal rights,” many will say.

And this is not just theoretical. After our verdict in Utah, I was able to pen an opinion piece in the New York Times that I had been wanting to publish for virtually my entire adult life. As I wrote:

Perhaps the jury verdict in our case is a sign that more people are rethinking whether their diets should include meat. Historically, many social movements have experienced sudden upswings in support, often in response to people taking risky actions that force the moral issue to the fore.

Our rescue in March 2017 revealed the tension between slaughtering animals for food and having compassion for them. The jury made the right choice. Our society eventually will, too.

It was as if the public’s imagination was expanding before our very eyes.

A solution with a problem

There is, however, a huge problem with the strategy of open rescue, despite these immense impacts. Very few people are taking up the strategy! Perhaps this is because the prosecutions have served some deterrent effect. Perhaps it’s the lingering impacts of COVID-19. But at the very moment in American history where the most important publications, and most powerful institutions, can’t stop talking about rescue, the movement for rescue is stalling.

This has to change. And it’s one of the reasons I will be traveling across the country in 2023 raising the banner of rescue — and teaching as many people as I can that all of us can be a part of the movement for open rescue.

I hope to see you out there sometime soon.