|

Today, I was arraigned on felony charges in Sonoma County, California, along with my co-defendants Cassie King and Priya Sawhney. The case, which will soon be scheduled for trial, has been a long time in the coming. Our first effort to aid animals at Sonoma County factory farms occurred in May 2018, when hundreds of us entered a massive egg farm — a “cage-free” and “humane” supplier to Whole Foods — and witnessed thousands of animals suffering in cages, in clear violation of California law. After months of tense negotiations with the government, in which we unsuccessfully pleaded with the authorities to protect animals from criminal abuse, we took action again in Sept 2018. This time, the site of our rescue was Petaluma Poultry, the largest organic poultry producer in the nation. Inside, we found animals collapsed on the ground; suffering from bloody wounds so deep that muscle and bone was exposed; and in some cases rotting to death. We set up a veterinary care tent outside of the factory farm and began providing emergency care — but the birds were torn from our arms and delivered to Sonoma County Animal Control.

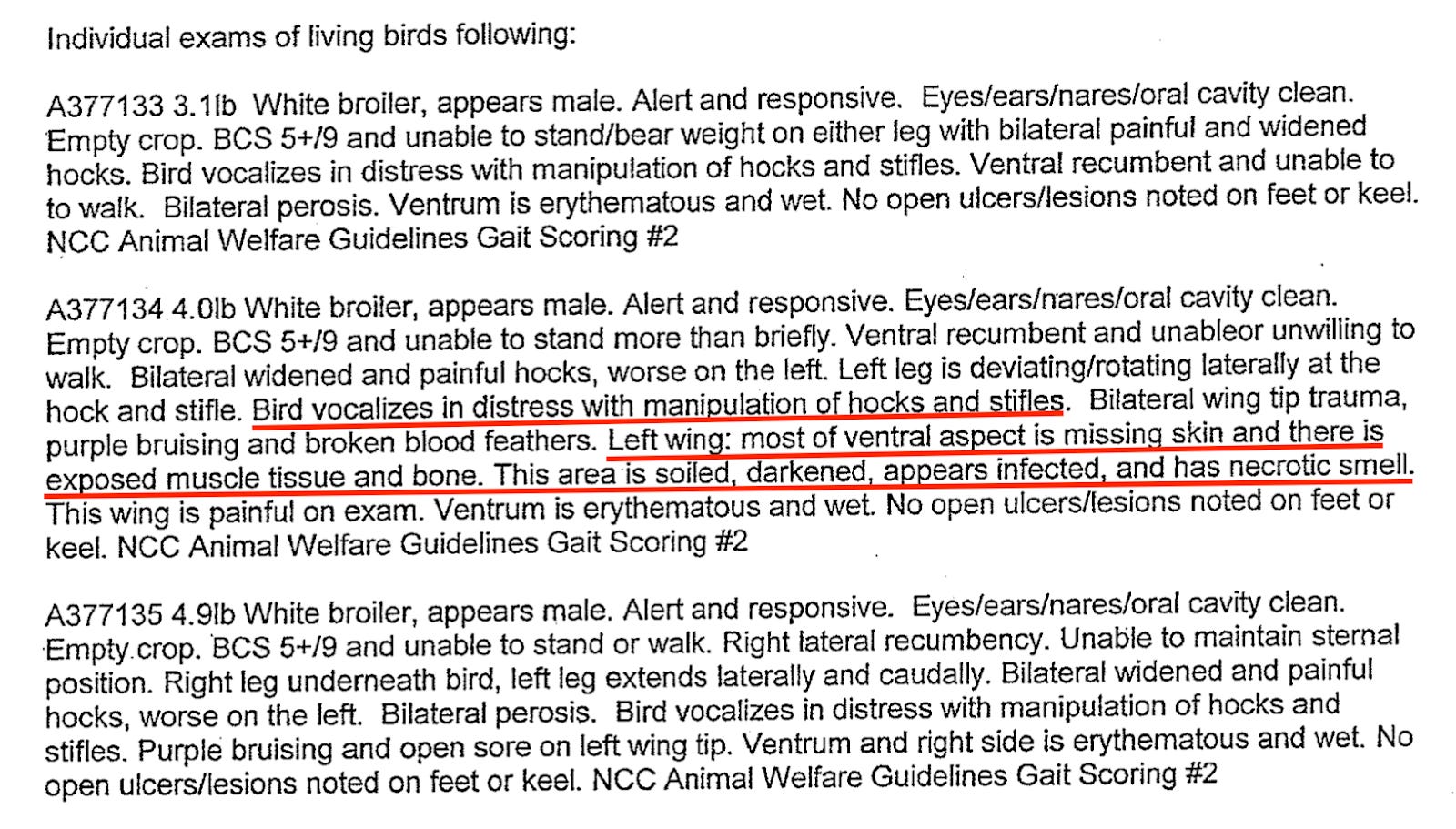

The state government’s own veterinarian confirmed our findings in a medical report — yet the authorities chose to charge 58 activists, rather than the poultry giant that had left animals to slowly starve to death.

The prosecution has now whittled down the 58 originally charged in the case to just four, which is why I was in court this week. But though I am proud to represent the animals in court — and move towards what we hope will be the next major victory for the right to rescue — every time I read the government’s report on the condition of the animals, I am left incredibly disturbed.

In some ways, this is a bit strange. We already knew, after all, that the animals were being horribly mistreated from our observations at the farm. Why should it matter that the state’s own veterinarian confirmed our concerns?

The reason the report is so important, however, is that illustrates one of the central pillars of the problem of evil. That problem, which philosophers and theologians have debated for thousands of years, can be put this way: if the world is good, why is it filled with so much evil? The answer to this question is in part that our society often makes evil seem normal or necessary. Even good people can commit atrocities under those conditions.

But the more important answer to the problem of evil is that systems can create grave injustice when there are no incentives for powerful people to do the right thing. Take the veterinary record above. In any remotely ethical legal system, individuals or corporations that inflicted such abuse would be stopped; law enforcement or prosecutors who stoped this abuse would be rewarded.

Yet that is the exact opposite of what is happening in Sonoma County. The law enforcement officials that ignore the abuse, or target the whistleblowers — such as former District Attorney Jill Ravitch or the new District Attorney Carla Rodriguez — continue to accumulate power and status, in part due to the support of ag-industry interest groups, such as the powerful local farm bureau. And there is virtually no incentive for any members of law enforcement to hold the factory farms accountable. They are among the largest private employers in the county.

Is it any surprise that even definitive evidence of criminal abuse is ignored, when the system is set up to encourage abuse and crush whistleblowers? The real surprise will occur when a prosecutor chooses to pursue a prosecution of factory farms, despite industry influence.

The explanation for the problem of evil, in short, is quite simple: evil thrives, even in a good world, when our systems encourage evil and suppress that which is good. The solution to this problem, in turn, is to invert this systemic corruption. We need systems that encourage that which is good and suppress actions that are evil. And the way to get to this result is to avoid the roadblocks that are preventing systemic change. That is precisely what the mechanism of a jury trial does.

By going to a random set of citizens, rather than an elected politician, we need not worry about the roadblocks caused by so-called “regulatory capture,” when powerful interest groups secure control over key aspects of our government. The factory farmers of Sonoma County do not even know who the members of the jury are; they’d be hard pressed to try to corrupt them.

By forcing a legal decision on the right to rescue, we also avoid the problem of “regulatory inertia,” when institutions resist change by imposing a dizzying number of bureaucratic obstacles. The vast majority of Californians do not want animals to be abused, yet our government has made it virtually impossible to even figure out how animals are being treated, much less stop their abuse. For example, there is no statewide inspection system for factory farms, and even when laws have been passed to protect farm animals, the government plays a game hot potato with allegations of criminality by the industry. We saw this firsthand when we reached out to dozens of state agencies in 2016, after Prop 2 when into effect, and could not find a single agency that was willing to even take responsibility for investigating violations of that law.

In contrast, when activists voluntarily subject themselves to prosecution, on the grounds that they are trying to protect animals from the very abuses that the law supposedly forbids, they force the government to take action. They force the government, and indeed our entire society, to make a decision on who they’d like to side with: the animal abusers, or the animal rescuers?

As I wrote in the New York Times after the Smithfield verdict, “Our rescue [of two piglets from Smtihfield] revealed the tension between slaughtering animals for food and having compassion for them. The jury made the right choice. Our society eventually will, too.” The key point that has become clear to me, however, is that the jury decisions in these rescue cases is not just a sign that change is happening.

It is a fulcrum from which we can drive forward that change.

—

Some quick updates for the week.

As with last week, I’m going live at 10:30 am PT this morning (Friday) to discuss Sonoma County and the Problem of Evil. Here’s the link. I’ll go into some more detail regarding the interesting discussions I overheard in court this week.

One of the most viral stories of the week involved animal rescue — in this case, a little girl who attempted to save her pet goat Cedar from slaughter. It’s a disturbing story but worth reading and amplifying — as the backlash against what happened has reached the highest levels of media, including CNN.

I’ll be in Buffalo next week to represent Tracy Murphy and for a mini-summit on the Right to Rescue. The link is here if you’d like to join. I’ll be blogging more about Tracy’s case next week. Stay tuned. But suffice it to say, for now, that the case involves one of the most sordid miscarriages of justice that I have witnessed in my nearly 20 years in the law. The key thing with this case, however, as with Cedar’s case, is that it will be an opportunity for us to create change.

That’s all for the week!