| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW BRIEFING: The unmet needs of people on probation and parole |

| Date | April 3, 2023 2:45 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

The community supervision systems are failing their most important function.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for April 3, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Mortality, health, and poverty: the unmet needs of people on probation and parole [[link removed]] Unique survey data reveal that people under community supervision have high rates of substance use and mental health disorders and extremely limited access to healthcare, likely contributing to the high rates of mortality. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Alexi Jones

Research shows that people on probation and parole have high mortality rates: two [[link removed]] and three [[link removed]] times higher than the public at large. That certainly suggests that our community supervision systems are failing at their most important — and basic — function: ensuring people on probation and parole succeed in the community.

With a similar approach to our recent series regarding the needs of people [[link removed]] incarcerated in state prisons [[link removed]], we did a deep dive into the extensive National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [[link removed]]. The results of this survey, administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), provide key insights into these specific — and often unmet — needs faced by people under community supervision. Because this survey asks respondents if they were on probation or parole in the past 12 months, this dataset comes closer than any other source to offering a recent, descriptive, nationally representative picture of the population on probation and parole.

The data that we uncovered — and the analyses of this same dataset by other researchers discussed throughout — reveal that people under community supervision have high rates of substance use and mental health disorders and extremely limited access to healthcare, likely contributing to the high rates of mortality. Moreover, the data show that people on probation and parole experience high rates of chronic health conditions and disability, are extremely economically marginalized, and have family obligations that can interfere with the burdensome — often unnecessary — conditions of probation and parole.

Substance use and mental health

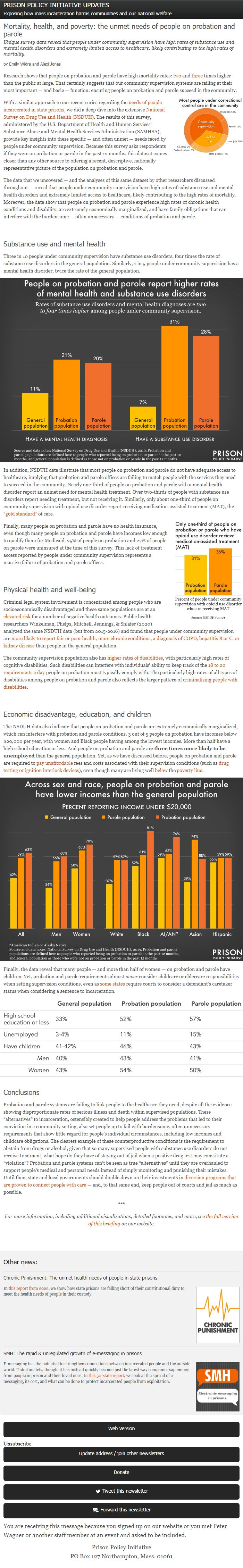

Three in 10 people under community supervision have substance use disorders, four times the rate of substance use disorders in the general population. Similarly, 1 in 5 people under community supervision has a mental health disorder, twice the rate of the general population.

In addition, NSDUH data illustrate that most people on probation and parole do not have adequate access to healthcare, implying that probation and parole offices are failing to match people with the services they need to succeed in the community. Nearly one-third of people on probation and parole with a mental health disorder report an unmet need for mental health treatment. Over two-thirds of people with substance use disorders report needing treatment, but not receiving it. Similarly, only about one-third of people on community supervision with opioid use disorder report receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT), the “ gold standard [[link removed]]” of care.

Finally, many people on probation and parole have no health insurance, even though many people on probation and parole have incomes low enough to qualify them for Medicaid. 25% of people on probation and 27% of people on parole were uninsured at the time of this survey. This lack of treatment access reported by people under community supervision represents a massive failure of probation and parole offices.

Physical health and well-being

Criminal legal system involvement is concentrated among people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged and these same populations are at an elevated risk [[link removed]] for a number of negative health outcomes. Public health researchers Winkelman, Phelps, Mitchell, Jennings, & Shlafer (2020) analyzed the same NSDUH data (but from 2015-2016) and found that people under community supervision are more likely to report fair or poor health, more chronic conditions, a diagnosis of COPD, hepatitis B or C, or kidney disease [[link removed]] than people in the general population.

The community supervision population also has higher rates of disabilities [[link removed]], with particularly high rates of cognitive disabilities. Such disabilities can interfere with individuals’ ability to keep track of the 18 to 20 requirements a day [[link removed]] people on probation must typically comply with. The particularly high rates of all types of disabilities among people on probation and parole also reflects the larger pattern of criminalizing people with disabilities [[link removed]].

Economic disadvantage, education, and children

The NSDUH data also indicate that people on probation and parole are extremely economically marginalized, which can interfere with probation and parole conditions. 3 out of 5 people on probation have incomes below $20,000 per year, with women and Black people having among the lowest incomes. More than half have a high school education or less. And people on probation and parole are three times more likely to be unemployed than the general population. Yet, as we have discussed before, people on probation and parole are required to pay [[link removed]] unaffordable [[link removed]] fees and costs associated with their supervision conditions (such as drug testing or ignition interlock devices [[link removed]]), even though many are living well below [[link removed]] the poverty line [[link removed]].

Finally, the data reveal that many people — and more than half of women — on probation and parole have children. Yet, probation and parole requirements almost never consider childcare or eldercare responsibilities when setting supervision conditions, even as some states [[link removed]] require courts to consider a defendant’s caretaker status when considering a sentence to incarceration.

Conclusions

Probation and parole systems are failing to link people to the healthcare they need, despite all the evidence showing disproportionate rates of serious illness and death within supervised populations. These “alternatives” to incarceration, ostensibly created to help people address the problems that led to their conviction in a community setting, also set people up to fail with burdensome, often unnecessary requirements that show little regard for people’s individual circumstances, including low incomes and childcare obligations. The clearest example of these counterproductive conditions is the requirement to abstain from drugs or alcohol; given that so many supervised people with substance use disorders do not receive treatment, what hope do they have of staying out of jail when a positive drug test may constitute a “violation”? Probation and parole systems can’t be seen as true “alternatives” until they are overhauled to support people’s medical and personal needs instead of simply monitoring and punishing their mistakes. Until then, state and local governments should double down on their investments in diversion programs that are proven to connect people with care [[link removed]] — and, to that same end, keep people out of courts and jail as much as possible.

***

For more information, including additional visualizations, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]]

In this report from 2022 [[link removed]], we show how state prisons are falling short of their constitutional duty to meet the health needs of people in their custody.

SMH: The rapid & unregulated growth of e-messaging in prisons [[link removed]]

E-messaging has the potential to strengthen connections between incarcerated people and the outside world. Unfortunately, though, it has instead quickly become just the latest way companies sap money from people in prison and their loved ones. In this 50-state report [[link removed]], we look at the spread of e-messaging, its cost, and what can be done to protect incarcerated people from exploitation.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for April 3, 2023 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

Mortality, health, and poverty: the unmet needs of people on probation and parole [[link removed]] Unique survey data reveal that people under community supervision have high rates of substance use and mental health disorders and extremely limited access to healthcare, likely contributing to the high rates of mortality. [[link removed]]

by Emily Widra and Alexi Jones

Research shows that people on probation and parole have high mortality rates: two [[link removed]] and three [[link removed]] times higher than the public at large. That certainly suggests that our community supervision systems are failing at their most important — and basic — function: ensuring people on probation and parole succeed in the community.

With a similar approach to our recent series regarding the needs of people [[link removed]] incarcerated in state prisons [[link removed]], we did a deep dive into the extensive National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) [[link removed]]. The results of this survey, administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), provide key insights into these specific — and often unmet — needs faced by people under community supervision. Because this survey asks respondents if they were on probation or parole in the past 12 months, this dataset comes closer than any other source to offering a recent, descriptive, nationally representative picture of the population on probation and parole.

The data that we uncovered — and the analyses of this same dataset by other researchers discussed throughout — reveal that people under community supervision have high rates of substance use and mental health disorders and extremely limited access to healthcare, likely contributing to the high rates of mortality. Moreover, the data show that people on probation and parole experience high rates of chronic health conditions and disability, are extremely economically marginalized, and have family obligations that can interfere with the burdensome — often unnecessary — conditions of probation and parole.

Substance use and mental health

Three in 10 people under community supervision have substance use disorders, four times the rate of substance use disorders in the general population. Similarly, 1 in 5 people under community supervision has a mental health disorder, twice the rate of the general population.

In addition, NSDUH data illustrate that most people on probation and parole do not have adequate access to healthcare, implying that probation and parole offices are failing to match people with the services they need to succeed in the community. Nearly one-third of people on probation and parole with a mental health disorder report an unmet need for mental health treatment. Over two-thirds of people with substance use disorders report needing treatment, but not receiving it. Similarly, only about one-third of people on community supervision with opioid use disorder report receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT), the “ gold standard [[link removed]]” of care.

Finally, many people on probation and parole have no health insurance, even though many people on probation and parole have incomes low enough to qualify them for Medicaid. 25% of people on probation and 27% of people on parole were uninsured at the time of this survey. This lack of treatment access reported by people under community supervision represents a massive failure of probation and parole offices.

Physical health and well-being

Criminal legal system involvement is concentrated among people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged and these same populations are at an elevated risk [[link removed]] for a number of negative health outcomes. Public health researchers Winkelman, Phelps, Mitchell, Jennings, & Shlafer (2020) analyzed the same NSDUH data (but from 2015-2016) and found that people under community supervision are more likely to report fair or poor health, more chronic conditions, a diagnosis of COPD, hepatitis B or C, or kidney disease [[link removed]] than people in the general population.

The community supervision population also has higher rates of disabilities [[link removed]], with particularly high rates of cognitive disabilities. Such disabilities can interfere with individuals’ ability to keep track of the 18 to 20 requirements a day [[link removed]] people on probation must typically comply with. The particularly high rates of all types of disabilities among people on probation and parole also reflects the larger pattern of criminalizing people with disabilities [[link removed]].

Economic disadvantage, education, and children

The NSDUH data also indicate that people on probation and parole are extremely economically marginalized, which can interfere with probation and parole conditions. 3 out of 5 people on probation have incomes below $20,000 per year, with women and Black people having among the lowest incomes. More than half have a high school education or less. And people on probation and parole are three times more likely to be unemployed than the general population. Yet, as we have discussed before, people on probation and parole are required to pay [[link removed]] unaffordable [[link removed]] fees and costs associated with their supervision conditions (such as drug testing or ignition interlock devices [[link removed]]), even though many are living well below [[link removed]] the poverty line [[link removed]].

Finally, the data reveal that many people — and more than half of women — on probation and parole have children. Yet, probation and parole requirements almost never consider childcare or eldercare responsibilities when setting supervision conditions, even as some states [[link removed]] require courts to consider a defendant’s caretaker status when considering a sentence to incarceration.

Conclusions

Probation and parole systems are failing to link people to the healthcare they need, despite all the evidence showing disproportionate rates of serious illness and death within supervised populations. These “alternatives” to incarceration, ostensibly created to help people address the problems that led to their conviction in a community setting, also set people up to fail with burdensome, often unnecessary requirements that show little regard for people’s individual circumstances, including low incomes and childcare obligations. The clearest example of these counterproductive conditions is the requirement to abstain from drugs or alcohol; given that so many supervised people with substance use disorders do not receive treatment, what hope do they have of staying out of jail when a positive drug test may constitute a “violation”? Probation and parole systems can’t be seen as true “alternatives” until they are overhauled to support people’s medical and personal needs instead of simply monitoring and punishing their mistakes. Until then, state and local governments should double down on their investments in diversion programs that are proven to connect people with care [[link removed]] — and, to that same end, keep people out of courts and jail as much as possible.

***

For more information, including additional visualizations, detailed footnotes, and more, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons [[link removed]]

In this report from 2022 [[link removed]], we show how state prisons are falling short of their constitutional duty to meet the health needs of people in their custody.

SMH: The rapid & unregulated growth of e-messaging in prisons [[link removed]]

E-messaging has the potential to strengthen connections between incarcerated people and the outside world. Unfortunately, though, it has instead quickly become just the latest way companies sap money from people in prison and their loved ones. In this 50-state report [[link removed]], we look at the spread of e-messaging, its cost, and what can be done to protect incarcerated people from exploitation.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor