|

What I Learned from the World’s Most Unflappable Cat

Courage sometimes comes in small packages. That can teach us all about how to be brave.

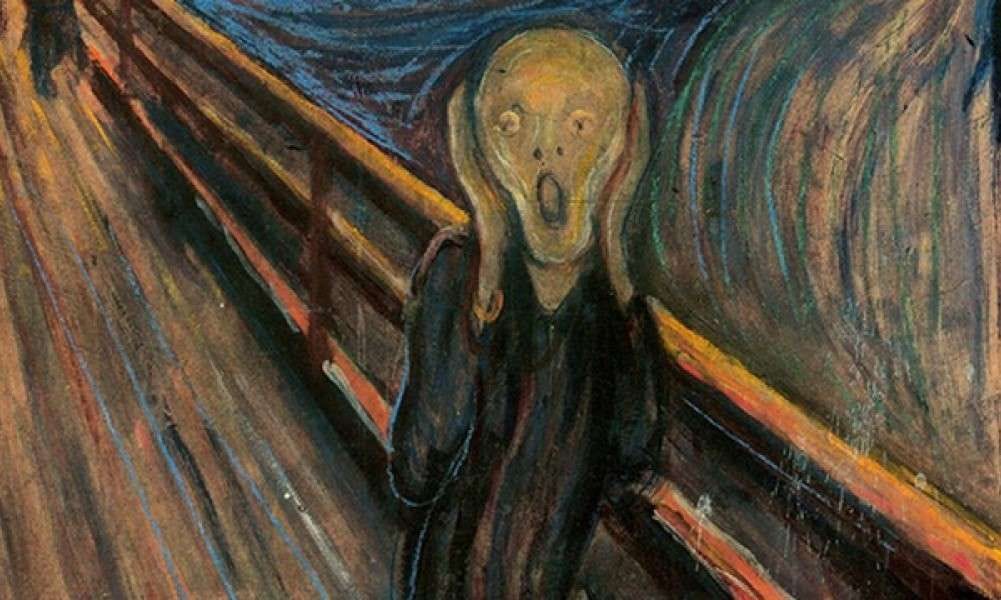

Fear is the primordial emotion. When the first vertebrate animals appeared on this earth 500 million years ago, fear was among the most important neurological innovations that helped them survive. Microorganisms had, for billions of years, developed ways to avoid things that could cause them harm, e.g., a simple chemical avoidance signal: “Move Away.” But as these tiny creatures evolved, their bodies (and minds) became larger and more complex, requiring the coordination of appendages, organs, and billions of cells. The simple chemical avoidance signals could no longer do the trick. It was not until the evolution of fear that larger, multicellular organisms – like animals – could organize their entire biological apparatus to avoid impending threats. Fear was like a flashing danger sign that would warn every part of an animal’s body that it was time for “fight or flight.”

And yet fear has, in many ways, gone haywire. The threats that we once faced – saber-toothed tigers, venomous snakes, and (above all) murderous bands of other human beings – no longer lurk around every corner. There was a time in our species’s history where as many as 12% of human beings died by lethal violence, surging to 30% in times of war. In contrast, today, the rate of lethal violence in the United States (which has among the highest homicide rates in the developed world) is a paltry 0.007%. The reduction in lethal violence is one of the greatest success stories in human history. And the evolutionary response to this violence – fear – seems quaint and outdated.

Yet fear still controls us. It pervades our politics, our communities, and even our individual emotional health. Trump rages about murderous Mexicans, and we believe him. The news media frightens us with stories of mass shootings, and we listen. And even our brain, which evolved to treat experiences with unfamiliar human beings as dangerous, tricks us into believing the worst in the people around us. This is true when they are engaged in utterly innocent acts, e.g., giving aid to help sick and injured animals.

Fear is the reason that anxiety is increasing across the globe to historic highs; the reason that levels of trust have declined to historic lows; and the reason that civil strife is spreading in societies that once seemed stable and kind. Fear is driving these negative changes despite the fact that we are living (objectively speaking) in an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity.

The solutions to this problem have been the subject of countless studies and dissertations. Entire fields of psychiatry and sociology and political science have been devoted to the problem of fear. And yet what I have learned, over the last 20 years, is that the solution to fear was right under my nose.

And the one who found it was my cat.

—

Joan Sawhney Hsiung was born on the streets of Chicago in late 2004, and was found in a box in the Chicago winter after his biological mother was lost just a week into life. One might not have thought that a living being born from these humble beginnings could make such a remarkable discovery. And yet that is exactly what Joan found: the cure for fear. That cure came in two parts: the first was a relentless goodwill, even when bad things unfolded in his life; the second was an adventurousness, the desire to venture into the unknown, even when his abilities were limited and his strength was weak. I saw him discover this cure, not only because I witnessed him overcome the perils of fear firsthand. But because he taught me to do the same.

This has been on my mind because, on February 24, 2023, Joan passed away after a difficult battle with pancreatitis. It’s been hard to explain the impact this had on me. I’ve tried saying, “It’s like I’ve lost an arm or a leg.” But the loss of even a physical body part doesn’t capture what’s gone with Joan’s death. Because Joan was a part of me, and I was a part of him.

My hope is that, by sharing what that meant to me, that loss can be partially restored.

—

I was a fearful child growing up. The kids at school made fun of me for being fat, unfashionable, and Chinese. But animals gave me solace. I would pet the neighborhood dogs; sing to the neighborhood sparrows; and have long conversations with the frogs in the creek.

“The animals like me,” I told myself. “So who cares if no one else does.”

Never mind that none of them appeared to recognize me. They did not show malice towards me, or try to hurt me. And, for a frightened child, that was enough.

Except for the cats. The neighborhood cats would give me an evil eye and run away the moment I approached. The one cat I knew personally – the pet of one of the rare Chinese families that allowed a non-human animal in their house – seemed intent on ending my life. She would hiss menacingly if I came in the room, bearing sharp claws and teeth, and refuse to allow me anywhere near her. For a child whose identity was based on being loved by animals, it was devastating.

“I hate cats,” I would say. “I’m not even sure they’re animals!”

“But then what are they?” my mom would ask.

“Probably aliens,” I would reply. “Maybe monsters from hell.”

And so even as I collected all manner of creatures, as an amateur animal rescuer from childhood to my early 20s, I never bothered to even touch a cat.

Until one fateful day in late 2004. I was in my second year of law school, and struggling to make it. I had already been called into the Dean’s office for skipping an exam. I was depressed, lonely, and desperate for some meaning in life. I began volunteering at the Chicago pound on the weekend. But I never entered the cat room. It was small and pitiful, with only a few dozen animals out of many thousands surrendered to the pound every year.

Most of the cats who entered the pound did not make it out alive. That depressing fact, and my childhood distaste of cats, led me to almost entirely ignore the pound’s feline wards.

Then Joan came into my life.

—

“There’s three of them,” the volunteer director said. “Can you take them? They’ll die or be killed if you don’t.”

I peered into the box he was holding and saw 3 tiny kittens, each smaller than my hand. One looked up and cried pitifully. The other two stumbled and reached their tiny paws out towards me.

I had no business taking in three kittens. I had never raised a cat before, much less 3 infants who needed to be bottle fed. I was barely able to take care of myself, surviving on ramen and potato chips and hardly showering or changing my clothes. And perhaps worst of all, I had just taken in another animal: a traumatized pit bull, Natalie, rescued from a fighting circle. Taking in 3 vulnerable beings who would need constant attention to survive, with a violent pit bull in the same studio apartment, seemed like a terrible idea.

And yet the volunteer director insisted.

“So will you take them? It’s the only way they’ll survive.”

I didn’t have a choice.

—

Caring for cats seemed alien to me.

“I guess they poop inside,” I told Natalie. “I hope you don’t mind.”

I placed the box in the closet, and hoped that the cats would never leave that corner of the house. Two of them, Flash and Stripe, obliged. But, as I wrote last month, there was one who would not.

[F]rom the moment he walked into my home, Joan showed bravery that seemed impossible.

While the other two kittens huddled in a dark, warm box in the closet, Joan ventured out into my apartment, and wandered into the darkest, coldest room — the bathroom. The creepy sounds of the Chicago wind, blowing against the oddly constructed windows in a way that sometimes scared even me, gave him no pause.

Then he tottered out and saw my dog Natalie. Natalie was a recent rescue herself — a traumatized pit bull mix rescued from a dog fighting ring. She snarled and bore her teeth at Joan, and for a moment, I was terrified. Was Natalie about to strike? Had I made a terrible mistake?

But Joan gave absolutely no heed. [He] walked right up to Natalie and tried to climb on top of her, as I held Natalie’s head and jaws back. And something amazing happened. Natalie laid her head back down. She realized that Joan was no threat, and let Joan walk all over her. And for 13 years, the two were not just friends; they were brother and sister, inseparable until the day Natalie died.

But the scariest animal of them all was yet to come: me. I had never taken in a cat before. I used to say to everyone who would talk to me — which was not many — that I hated cats. Cats were like the cool kids at school, and I was definitely not cool! I was an angry young man, struggling to make it through law school and bitter towards the world, and 100+ times larger than this tiny kitten smaller than the palm of my hand. Surely, this kitten would see me for who I was: a cat-hating behemoth. Surely, he would be afraid.

But as I sat there, watching him crawl, he turned toward me and walked straight into my lap. He nestled his little head into my thigh, finding the warmth of my body comforting. And when I touched his head, he looked up at me, purring, and said something to me, with his face and his eyes, I will remember until the day I die:

“I trust you. Thank you for saving me."

That look transformed me. I was no longer a cat-hating behemoth, fostering kittens with a deep frustration and anxiety. I was suddenly a proud papa, looking at the newest member of my family.

“Thank you for taking me into your family," the kitten said, with the look in his eyes.

I named him Joan. He was my little Joan of Arc, brave to the death; never afraid. (He also turned out to be a boy, 6 months later, but it never occurred to me to change his name.)

There were a few things that I found remarkable about this. The first is that Joan had goodwill for Natalie, and for me, despite the aggression and dislike we showed to him. And this was key to combating his – and my – fear. By going out into the world with love and hope, even in the face of devastating experiences in life, Joan was able to overcome the terror that would have afflicted most beings in his state.

But there was something else about Joan, and adventurousness and curiosity, that was just as important. When he ventured into the dark, icy bathroom, or into the lap of two angry animals with no prior compassion for cats, he did so not know what would happen. But his yearning to approach what was uncertain, and see what it might hold, helped him overcome his fear.

And I remember that first night, sitting and watching him, as he continued to explore (while the other kittens slept), and thinking to myself: this is the key to being brave. Goodwill and a sense of adventure are all it takes.

Joan continued this path for the next 18 years of his life. There was the time he disappeared for two weeks, after escaping over our backyard fence in Berkeley. I scoured the neighborhood, calling to him desperately and warning that the world was a dangerous place. But when we had nearly lost all hope, he showed up in our backyard as if nothing had happened at all. He was a little skinnier, and had lost his collar. But when he strolled into the house, he looked at me as if nothing had changed.

“What, Dad? I was just hanging out. Don’t get so scared.”

Then there was the time that Joan lost his sight. We still don’t know how or why, but blood began filling up Joan’s eyes. His blood pressure skyrocketed, and his retinas detached. The world went completely dark. When the vet told me that he would never see again, I burst into tears. My little adventurer, I thought, would never explore again.

But within weeks, Joan proved me wrong. He began climbing over all manner of obstacles in the house, despite being completely blind.

He even began venturing outdoors again, and if not for my careful supervision probably would have explored the entire city of Berkeley – even completely blind. The 1.5 years of caring for Joan in that state were some of the best and most interesting of my life. And even as I continued to take in strange creatures, Joan never seemed fazed. He was always brave.

There is so much more I could share about Joan’s life. But this essay is already becoming quite long, and I want to tie what I learned from, and observed in Joan, to the events of the last few weeks.

Two dear friends and activists, Alicia Santurio and Alexandra Paul, faced prosecution in Merced County, for merely giving aid to two sick and dying chickens in the back of a slaughterhouse truck. There has been so much written about this case already, including a beautiful synopsis by Marina Bolotnikova at Vox, and a compelling column by Farhad Manjoo at the New York Times. But one thing that has been missing from the coverage, for the most part, is how Alicia and Alexandra came to be so brave. So many others would not have been able to do what they did, so brazenly – openly remove animals from a slaughterhouse truck, even with the threat of impending prosecution. Fewer still would have taken the case to trial. Each defendant received a favorable plea bargain that would have avoided any jail time.

And yet the two women persisted. They fought. And they won. And I think a huge part of the reason why was the same as the reason that Joan was brave. Each defendant has goodwill towards the world. They believed in the goodness of their fellow human beings, even in a world that seem cruel and dark. And they did not fear the uncertainty of trial. In some ways, each defendant saw the experience as an adventure. Alicia has told me many times, for example, that she enjoyed testifying – even when the prosecution was trying to trip her up and force her to admit something that would lead her to be jailed!

There are many beautiful and powerful things happening in the world right now, and that is increasingly true of animal rights. More exposure, education, and change are driving progress in unprecedented ways. But there is one fundamental stumbling block: fear.

I have noticed, in recent years, a shadow being cast over the animal rights movement. It’s not dissimilar from the shadow that was cast in the early 2010s, when activists who had heard of the ag gag laws, or the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, would reach out to me and ask if they could be prosecuted for terrorism for merely leafleting on a public street. Things are not quite that bad, in 2023, but there is a similar pall across the movement, and perhaps other social movements, too.

But this time, the fear is not driven primarily by the threat of prosecution. We have won two historic cases, after all, and even when we have lost, the punishment has not been nearly as severe as the punishments handed 15-20 years ago. The fear, in this case, is self created. It is cultural. It is spiritual. It comes from our own hearts.

And if we are to overcome it, we must learn what Joan learned, what Alicia and Alexandra learned. The world is not always a kind place, but we cannot battle cruelty with cynicism and hate. We can only battle it, and the fear in our hearts, by finding goodwill for those around us – even those who intend to hurt us. I was struck, recently, by an email one of our legal team members sent to the prosecution in the Foster Farms case. I will not share the exact details, for privacy reasons, but a prosecutor wrote back with a touching story about the loss of a beloved dog. We have to see this goodness in people if we hope to combat our own fear.

But we also must realize that uncertainty is not always bad. Sometimes, it provides a sense of adventure and even joy. Too often, animal rights activists suffer from neophobia – the fear of all that is new. This is true of the veteran animal lawyers who condemned us for pushing the law too far – refusing to believe that good people in our society would acquit us. It’s true of the nonprofit leaders that said we could never inspire the grassroots to fight – and risk themselves – for animals in the way that people have risked themselves for human justice for hundreds of years. And it’s even true of each of us, when we choose to stay away from tactics or people that seem alien to us – not realizing that those new concepts and relationships could not only create incredible change, but also give us personal joy.

Alexandra and Alicia did not fall victim to this fear, and neither did Joan. And if the world is going to overcome the existential threats it faces, more people will need to learn how to do this too. More people will need to learn how to not be afraid.

—

Some quick hits:

Weekly livestreams on Friday. I am going to start livestreaming on Fridays at 10:30 am and will kick it off by briefly discussing this blog. I have deep concerns that the animal rights movement, and our society more generally, is being not just held back, but decimated, by fear. But the goal of these livestreams is also to find out what things are on your mind – and what you’d like me to write about or discuss. You can join the livestream here.

Sonoma arraignment is next week. After nearly 5 years, we are finally, officially being arraigned on felony charges in Sonoma County. This case, which involved a mass open rescue at the largest organic poultry producer in the nation, is perhaps our most legally important one. I’ll be blogging about the case next Thursday, but let me know what questions you have to help guide what I write. The Sonoma mass open rescue was the subject of this pretty awful short documentary by VICE.

The Foster Farms summit from April 22-23. We have been having some great conversations with the jurors from the Foster Farms trial, and it’s looking like a few of them will join us for a legal summit at UC Hastings in San Francisco! Plan to join us on the weekend of April 22-23. I am confident there will be incredible insights revealed.

The Open Rescue Experience at the Animal Liberation Conference in June. DxE announced this week that I’ll be leading a training at the conference on open rescue. This will be the first time I’ve led the training at ALC since 2018. And it has been completely revamped, focused on creating an effective legal strategy from Day 1. You won’t want to miss this, regardless of whether you have an interest in going on trial yourself. Because it will teach you how you can use the trials to create change in your own community.

A new focus for The Simple Heart. A lot has changed with this blog, and the organization we founded around it. I still believe that distrust is a fundamental problem with the human condition. But I am also realizing that my comparative advantage, in fighting that problem, revolves around animal rescue. When we rescue the animals we rescue ourselves. Look out for more on TSH’s pivot towards rescue in the weeks to come.

Thanks to everyone for reading, and many apologies for the failures in providing regular content in the last few weeks. The Foster Farms trial took over my life. But I want to say, again, that I’m grateful to you all. Even when the odds have been looking impossible, knowing that so many folks support us makes all the difference in the world.